I often see writing about Canadian cities in my future: not for the current project, and probably not for the one after, but maybe the one after that. In a time foreseeable, anyway. The vision came again on our latest trip to Vancouver, as we stood in the Pacific Central Station, from which one could theoretically head east on a pretty illuminating cross-country rail trip. I don’t quite know what about Canada’s metropolises attracts me, but I suspect it has to do with their distinctively open brand of internationalism (as my residence in Los Angeles has much to do with its own, very different, brand of same). Pico Iyer, as usual, said it better before, and he said it, no less, in his inaugural Hart House lecture, “Imagining Canada”:

As I walked around [Toronto], stepping across centuries and continents each time I crossed a side-street, I found myself, as many people had told me I would, in the East Coast city of my dreams, the kind you see only in movies (in part, of course, because idealized visions of Boston or Washington or New York are generally set in Toronto, just as the San Francisco or Seattle of the world’s imagination is usually shot in Vancouver). I went to a ballgame at the SkyDome, I looked at “Indian-Pakistani-style Chinese” restaurants, I walked and walked among the shifting colors and sovereignties of Bloor Street, and everywhere I saw a confluence of tribes not so very different from what I would encounter in The English Patient. [ … ] In some ways, not so surprisingly, what I was seeing was a place with both the sense of history (and so the sense of irony) of the England where I’d grown up, and the sense of future (and so the sense of expansiveness) of the America where I’d come to make a new life.

Regarding Vancouver specifically, a town I visited semi-regularly while growing up in Seattle, I’d come this time to record interviews for Notebook on Cities and Culture and get a handle on that celebrated variant of urbanism known as Vancouverism. Surprisingly for an -ism, it’s gotten results. “Why can’t we have this?” an Angeleno may find himself repeating on a trip to Vancouver: about the rail connection to the airport, about the smooth pavement, about the ocean visible from downtown, about the abundance of sweet-potato sushi rolls. I felt the impulse myself, but if any practice clouds my perception of a city — one I visit, or my own — lamentation does, and badly. Still, as a city on the whole clean, verdant, prosperous, and thoughtfully laid out, if burdened by real-estate values that consume the bulk of residents’ income and conversational bandwidth alike, Vancouver has, by North American standards, a great deal going for it.

Yet almost every Vancouverite I talk to, no matter how freely they chose the life, comes around to the same — not conclusion, exactly, but — tag of resignation: they find the place a little boring. Though always happy to return, they in the first place require regular escape from not just the city but the entire country. Having never spent more than a week in Vancouver at a stretch, I can understand this only in the abstract; I’ve never actually felt the mild form of oppression to which the well-known nickname “No Fun City” sticks. But it doesn’t really surprise me. While I don’t believe, exactly, that Peace, Order, and Good Government — not to mention smoothly paved streets — must necessarily suppress cultural vibrancy and raise seething malaise, I do subscribe, at least for the moment, to a double-edged-sword theory of cities: that each one’s disadvantages are not just balanced by, but produced by, its disadvantages, and vice versa.

A friend in Japan put it best: the same force that makes the trains run on time makes citizens occasionally jump in front of them. As of November 2008, Vancouver’s Skytrain, an impressive and reliable-seeming (if commuter-oriented) rapid transit system, had racked up 54 deaths, 44 of them suicides. Writing for A Los Angeles Primer about the Blue Line, which runs between downtown and Long Beach, I found that train’s body count had risen past 100; this alongside the stream of malfunctions announced daily on the official Metro Twitter feed. Looking closely at the Blue Line, you can only with great effort ignore signs of the attitude that considers transit only for people too poor or infirm to have a choice in the matter — “captive riders,” in the industry lingo. You get that in a vast, fragmented city like Los Angeles. In a vast though not particularly fragmented city like, to draw from my own experience, Osaka — or, shall we say, in a not particularly fragmented culture like Japan — you don’t.

In a city like Vancouver, whose fragmentation ranks somewhere in between, you do see in public spaces roughly what a Londoner might think of as a mixing of the classes, though though local boy Douglas Coupland still writes of the notion that, even in his hometown, “car ownership equals citizenship.” But you also get a Topshop integrated into a subway station, whereas Los Angeles’ Topshop just opened in The Grove, a famously ersatz urban space with only one transit element of note: a double-decker trolley that rolls back and forth through the mall itself. (Still, Yubin Kim from Wonder Girls calls it her favorite place in the city, so I suppose I can’t call it a total failure.) These things all get me considering what I instinctively gauge — the proximity of “high” and “low,” the number non-impoverished riders on buses and trains, the availability of Korean food — when I turn up in a city I haven’t visited before, or at least haven’t seen in a while. What, in other words, do I use as my urban tests? I think, for example, of Jan Morris’ “smile test”:

This is the system I employ to gauge the responsiveness of cities everywhere, and it entails smiling relentlessly at everyone I meet walking along the street–an unnerving experience, I realize, for victims of the experiment, but an invaluable tool of investigative travel journalism. Vancouver rates very low in the Smile Test: not, heaven knows, because it is an unfriendly or disagreeable city, but because it seems profoundly inhibited by shyness or self-doubt.

Pay attention now, as we put the system into action along Robson Street, the jauntiest and raciest of Vancouver’s downtown boulevards. Many of our subjects disqualify themselves from the start, so obdurately do they decline eye contact. Others are so shaken that they have no time to register a response before we have passed by. A majority look back with only a blank but generally amenable expression, as though they would readily return a smile if they could be sure it was required of them and if they were quite certain that the smile was for them and not somebody else.A few can just summon up the nerve to offer a timid upturn at the corners of the mouth, but if anybody smiles back instantly, instinctively, joyously, you can assume it’s a visiting American, an Albertan or an immigrant not yet indoctrinated.

In this 1992 essay, Morris makes the now-standard assessment of Vancouver about as well as I can imagine it made. “After five days, you see, I was pining for imperfection or excess,” she writes. “I pined for the dingy, the neglected and the disregarded old, for a scowl now and then, for swagger, for flash. I pined for blacks, punks, French Canadians. I would not go so far as to say I pined for AT&T, but I did occasionally wish those girls would press the wrong button on the Grouse Mountain tramway or that the SeaBus would break down in mid-crossing and be carried, floundering ludicrously, out to sea.”

Yet, having tired of this story about Vancouver as a place beautified and livablized into a kind of mediocrity, I struggle to say or at least think something else about it myself. I do admit that, especially coming from the likes of Los Angeles, one does tend to assume that a city so orderly and tree-filled must have become that way in compensation for basic, and major, faults. And indeed, any city developed under big ideas — such as that which decreed that most high-rise builders must pick a proper shade of sea green — inevitably brews its on flavor of Kool-Aid for its boosters to drink. Having drunk the Vancouver-Aid, you may well still complain about the city’s feeling of remoteness — and that means remoteness within Canada.

So in writing about Vancouver, now or in the years ahead, I sense a challenge — a pleasant, nature-proximate, livable challenge. What to say about the city in the 21st century? Morris herself envisioned the Vancouver of 2042 “much as it is today, only less so. Less pristine and meticulous, that is, for even Vancouver cannot permanently escape the urban rot. Less fresh-faced and imperturbable, as the ethnic balance shifts. Less reserved and unassertive, perhaps, as competition bites. Less orderly and uptight, as the legacy of the British wanes at last. Less restrained and considerate, as the free trade in violence and vulgarity inexorably proceeds. Less beautiful? I think not–nothing can really spoil the natural glory of it. Less boring? Oh certainly, sure to be less boring.” But in 2013, I wonder if the time hasn’t come to replace the concept “boring” with, well, a more interesting one.

As soon as we landed, we met my friend Chris, who five years ago emigrated to Vancouver from the states, at the city’s airport — one much heralded, of course, for its comfort and attractiveness. He told us to meet him under a Bill Reid sculpture of First Nations people in a canoe. “Just say Indians,” I may or may not have replied, but we in any case ultimately found ourselves under the same massive stone boating party about which Talking Head and bicycle diarist David Byrne blogged in 2009. “An image of this sculpture is on the Canadian $20 note,” he writes. “An old English lady is on the front.” Though short, Byrne’s post points toward other ways to write about modern Vancouver. He tells of a chat about the future of Vancouverism with mayor Gregor Robertson, who “claimed that the Vancouver formula is far better for the community than almost any other city’s, which has made for some very livable urban hoods.” Alas,

Being a New Yorker, maybe I’m sadly more cynical. In spite of how well things are going in New York, the balance is always precarious. I offered that the economic downturn might slow development a bit, and turn out to be an opportunity for all folks, wealthy and less wealthy, to reassess what kind of town they want to live in and what kind of life they want — given the unexpected (for some) break in the years of relentless acquisition and striving. “Given a second to think about it, would people really choose to live in vertical ‘rabbit hutches’?” I said, glancing out the window at a new condo tower with only a few lights on. “Well-appointed rabbit hutches,” Robertson replied.

We should, in retrospect, have experienced the city in a more Byrneian fashion: on two wheels. Chris also suggested this, and strongly, but I let my interviewing schedule muck it up. Hence the travel rule I’ll now put into effect: rent the bikes first. That, I think, will give me the clearest possible perspective on each city I visit, even ones as difficult to observe from a fresh angle as Vancouver. If you seek those like I do, you might consider keeping up with Reflecting Vancouver, the “West Coast urban weblog” Chris started up not long after we returned to Los Angeles. That brings a second rule to mind. Rent the bikes first, sure, and then listen very closely to the locals. They don’t all talk just about real estate.

[Previous diaries: Mexico City 2013, Portland 2013, Kansai 2012, Seattle 2012, Portland 2012, San Francisco 2012, Mexico City 2011]

Colin Marshall sits above Hastings Street in Vancouver, British Columbia with Gordon Price, Director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University, former Councillor for the City of Vancouver, and creator of the electronic magazine Price Tags. They discuss his personal definition of “Vancouverism”; his city as a mid-20th-century version of 19th-century city-building; the balance of trying to maintain the place’s Edenic qualities while shipping out its natural resources; the D-word of density, and whether Vancouver’s West End ever really had the highest density in North America; how built environments age in place, passing from horror to heritage; how building for the car worked, until it didn’t; “stroads,” like Los Angeles’ La Cienega, which combine the worst of streets with the worst of roads; budgets as the sincerest form of rhetoric; the role technology plays in our newfound adoption of transit; whether Los Angeles could become “the Vancouver of 2020” — or maybe 2030; how New York came from the brink, and what he saw during its decline; whether the Utopian question of how to prevent dullness matters to Vancouver; the erotic power of the surreptitious, the illegal, and whatever you can’t regulate; the element of his personal life that got him interested in cities, where he used to find them emblems of what had gone wrong in society; gay men as urban pioneers; and how cities can do better with whatever they’ve already got.

Colin Marshall sits above Hastings Street in Vancouver, British Columbia with Gordon Price, Director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University, former Councillor for the City of Vancouver, and creator of the electronic magazine Price Tags. They discuss his personal definition of “Vancouverism”; his city as a mid-20th-century version of 19th-century city-building; the balance of trying to maintain the place’s Edenic qualities while shipping out its natural resources; the D-word of density, and whether Vancouver’s West End ever really had the highest density in North America; how built environments age in place, passing from horror to heritage; how building for the car worked, until it didn’t; “stroads,” like Los Angeles’ La Cienega, which combine the worst of streets with the worst of roads; budgets as the sincerest form of rhetoric; the role technology plays in our newfound adoption of transit; whether Los Angeles could become “the Vancouver of 2020” — or maybe 2030; how New York came from the brink, and what he saw during its decline; whether the Utopian question of how to prevent dullness matters to Vancouver; the erotic power of the surreptitious, the illegal, and whatever you can’t regulate; the element of his personal life that got him interested in cities, where he used to find them emblems of what had gone wrong in society; gay men as urban pioneers; and how cities can do better with whatever they’ve already got.

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with

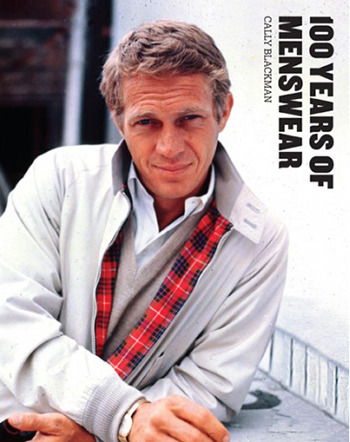

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.