Wednesday, December 11, 2013

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast I have a conversation with A. Scott Berg, author of books on Max Perkins, Charles Lindbergh, Samuel Goldwyn, Katharine Hepburn, and now, with Wilson, on the 28th president of the United States. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

In the early 1980s, well before his doggedly exploratory restaurant criticism in the Los Angeles Times and the Weekly made him famous, Jonathan Gold gave himself a mission: “to eat at every restaurant on Pico Boulevard and create a map of the senses that would get me from one end to the other.” This rigorous mandate demanded that he has at least a few bites of food in every one of Pico’s eateries, of every kind, in order. “As often happens with these restaurants, they close down,” he explains on a 1998 “This American Life” broadcast, “so if I’d gone two miles and a restaurant I’d gone to had closed down and opened up again, I would have to go and eat at that restaurant before the next one.” He soon “became obsessed with the idea of Pico Boulevard. Almost every ethnic group that exists in Los Angeles, you can find on Pico,” from “specific blocks that are Guatemalan, Nicaraguan blocks, Salvadoran blocks” to “parts you can drive a mile without seeing a sign that isn’t in Korean” to “a huge concentration of Persian Jews that came over around the time the Ayatollah took power. I don’t think there’s another street in Los Angeles quite like it.”

The young Gold’s mission strikes me as an appealingly and almost quintessentially Los Angeles journey to undertake: ambitious, hedonistic, self-assigned, and totally Sisyphean. He never finished it, but no one could have. He mentions the here-today-gone-tomorrow nature of the businesses on Pico, which goes a fair way toward explaining the difficulty of completist eating. When you multiply that by the boulevard’s sheer length, difficulty becomes impossibility. In most other American cities, having eaten everywhere on a particular street would sound mundane, almost dull, less an accomplishment than an admission that you don’t get very far afield. But Los Angeles’ streets present another experience entirely, something the Dutch novelist and traveler Cees Nooteboom discovered when he came to Los Angeles for a stay in Beverly Hills in 1973. “On the third day, I ventured outside,” he writes. “I walked, which was crazy — not because it is dangerous but because it does not make sense. In a city with streets longer than fifty kilometers, the measure of one foot is absurd, and so is the use of one’s feet as a means of transportation.”

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Vital stats:

Format: comments on Los Angeles and the changes therein, followed by interviews with those tied to the region’s past

Episode duration: 1h-1h30m

Frequency: weekly

I’ve never taken a trip with Esotouric, which offers “provocative and complex, but never dry” bus bus tours of greater Los Angeles which mix “crime and social history, rock and roll and architecture, literature and film, fine art and urban studies into a simmering stew of original research and startling observations” on such territories as “Hot Rods, Adobes, and Early Modernism,” “Haunts of a Dirty Old Man” (i.e. Charles Bukowski), and “Pasadena Confidential with Crimebo the Crime Clown.” Until such time as I cough up the sixty bucks to board an actual Esotouric bus, I’ll opted for the next best thing: You Can’t Eat the Sunshine [RSS] [iTunes], a weekly podcast hosted by the company’s proprietors, the husband-and-wife team of near-obsessive Los Angeles enthusiasts Kim Cooper and Richard Schave. Each episode opens with a local place-name-checking theme song by a ukulele-playing lady known as the Ukulady, who looks, as her site reveals, exactly like she sounds, thus embodying a perfect union of form and substance. The podcast on which she plays enjoys a similar alignment between its own expansive form and that of the city/county/”mega-region”/half of the state of California it examines.

You Can’t Eat the Sunshine doesn’t make the obvious choice of offering audio versions of Esotouric tours, but it surely burns as much gas each time out with its actual mandate: to track down unusual people — poets, craftsmen, professors, impersonators of historical figures — living in Los Angeles and its environs, most of whom have strong ties to the place’s past, and interview them. On some episodes this just means going downtown; on others it means rolling to Long Beach, Eagle Rock, UCLA, Downey, La Mirada, or Lake Elsinore, the names of which wear me out in the typing alone. “We were born here,” announces Cooper in the 90-second back-and-forth spoken intro that precedes the Ukulady, and indeed, I’ve come to notice a certain divide between native Los Angeles appreciators and those transplanted. I fall into the latter group, having moved here for no better reason than that it fascinated me more than any other city in America — well, that and its robust revival cinema scene — and now my current projects include not just a book on the place but an interview podcast more than half of whose episodes deal with Los Angeles. By all rights, I should have taken every available Esotouric journey already, if not up and launched a competing provocatively complex, research-and-observation-stewing bus tour company of my own.

Read the whole thing at Maximum Fun.

Colin Marshall sits down in the Copenhagen offices of Gehl Architects with founding partner Jan Gehl, architect, Professor Emeritus of Urban Design at the School of Architecture in Copenhagen, and author of books including Life Between Buildings, Cities for People, and How to Study Public Life. They discuss what important change occurred in Copenhagen in 1962, and what led to it; the midcentury “car invasion” in Europe and the first modern shopping mall’s construction in Kansas City; the re-emergence of the notion that “maybe pedestrians should walk”; the connectedness of walking in Copenhagen, which ultimately forms a “walking system”; the dullness of the anti-car position versus the richness of the pro-people one; the two movements of modernism and motorism, at whose intersection he found himself upon graduating from architecture school in 1960; what it meant to study “anti-tuberculosis architecture,” and what it meant to build for the old diseases rather than the new ones; his marriage to a psychoanalyst and ensuing interest in increasing architecture’s attention to people; how his PhD thesis became Life Between Buildings, and why that book has endured for over four decades in an ever-increasing number of languages; how first we form cities, and then they form us; what we can learn from Venice; the urban “acupuncture” performed on various American cities today; his long enjoyment of Melbourne; why we’ve only so slowly awoken to our dissatisfaction with the built environment; the loss of cheap petroleum and stable nuclear families, which propped up suburbia; how he and his team systematize and use their knowledge of cities to examine and assist the use of public space across the globe; and all he finds totally unsurprising about man’s use and enjoyment of place.

Colin Marshall sits down in the Copenhagen offices of Gehl Architects with founding partner Jan Gehl, architect, Professor Emeritus of Urban Design at the School of Architecture in Copenhagen, and author of books including Life Between Buildings, Cities for People, and How to Study Public Life. They discuss what important change occurred in Copenhagen in 1962, and what led to it; the midcentury “car invasion” in Europe and the first modern shopping mall’s construction in Kansas City; the re-emergence of the notion that “maybe pedestrians should walk”; the connectedness of walking in Copenhagen, which ultimately forms a “walking system”; the dullness of the anti-car position versus the richness of the pro-people one; the two movements of modernism and motorism, at whose intersection he found himself upon graduating from architecture school in 1960; what it meant to study “anti-tuberculosis architecture,” and what it meant to build for the old diseases rather than the new ones; his marriage to a psychoanalyst and ensuing interest in increasing architecture’s attention to people; how his PhD thesis became Life Between Buildings, and why that book has endured for over four decades in an ever-increasing number of languages; how first we form cities, and then they form us; what we can learn from Venice; the urban “acupuncture” performed on various American cities today; his long enjoyment of Melbourne; why we’ve only so slowly awoken to our dissatisfaction with the built environment; the loss of cheap petroleum and stable nuclear families, which propped up suburbia; how he and his team systematize and use their knowledge of cities to examine and assist the use of public space across the globe; and all he finds totally unsurprising about man’s use and enjoyment of place.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

I’ve taken my recent trips to and from Bunker Hill exclusively by stair, owing to the current shutdown of Angels Flight, the beloved funicular that, when operational, carries passengers up from Hill Street and back down again. It doesn’t go out of order often, but when it does it often stays that way for some time: a fatal 2001 accident put it out of commission for nearly eight years, and before that, in 1969, the redevelopment of Bunker Hill brought about its dismantling and subsequent storage for just under three decades. What kind of a city, this leads one to ask, struggles to keep even the world’s shortest railway — and one of its few icons, at that — in continuous operation? In my case, this question encourages the darkly methodical contemplation of Los Angeles’ other infuriating qualities, one after the other: its vast, often ridiculous distances; the shabbiness of so much of its built environment, mini-malls and otherwise; the barely explicable gaps in, and slowness of the rest of, its rapid transit system; the percentage of its surfaces covered by advertisements for movies whose distributors couldn’t pay me to watch.

But moments before I decide to pull up stakes, I turn around and behold a counterargument: Grand Central Market, the urban emporium that has, since 1917, provided downtown residents a place to buy their produce. More recently than that, it has provided them a place to buy a variety of moles, dried chiles, and herbal medicines. More recently than that, it has provided them a place to buy a quick office-worker’s lunch. More recently still, it has provided them a place to buy ten-dollar hamburgers, thirteen-dollar Cobb salads, and six-dollar soy lattes. At this particular moment, these almost parodic manifestations of gentrification — preparation of that six-dollar soy latte involves not actual soy milk, but “a special almond milk we make here” — coexist fascinatingly with what habitués sometimes call the “old” Grand Central Market, by which they mean Grand Central Market as a delivery system of cheap vegetables and even cheaper meals. China Cafe, the most prominent representative of this era, appears right up front, its neon signs advertising “CHOP SUEY” and “CHOW MEIN” visible as soon as you enter from Hill. Come at the right time, well before the families and tourists turn up, and on its stools, beneath its menu surely unchanged by the decades, you can still find a handful of old alcoholics huddled over morning trays of egg foo young.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with Classic Copenhagen blogger and photographer Sandra Høj. They discuss the city’s current enthusiasm for tree-cutting; the small things in Copenhagen that draw her eye, from pieces of street art to weird details on houses; how she started blogging in the wake of the Muhammad caricature crisis with an interest in disputing the global perception of Danes as living obliviously in a land of pastries and fairy tales; her mission to describe “the good, the bread, and the ugly” of Copenhagen; the Danish tendency to nag about problems; what time spent in “cozy” Amsterdam taught her about her “sexy” home city; what time spend in Paris taught her about how Copenhagen could better respect itself; the bewildering array of political parties putting signs up all over the city, and how rarely their actions match their words; her desire for children to grow up in the same Copenhagen she did; the evolution of Amager, also known as “the Shit Island”, and what gentrification looks like elsewhere in the city; the scourge of Joe and the Juice; and her continuing search outward for more “traces of life” in Copenhagen.

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with Classic Copenhagen blogger and photographer Sandra Høj. They discuss the city’s current enthusiasm for tree-cutting; the small things in Copenhagen that draw her eye, from pieces of street art to weird details on houses; how she started blogging in the wake of the Muhammad caricature crisis with an interest in disputing the global perception of Danes as living obliviously in a land of pastries and fairy tales; her mission to describe “the good, the bread, and the ugly” of Copenhagen; the Danish tendency to nag about problems; what time spent in “cozy” Amsterdam taught her about her “sexy” home city; what time spend in Paris taught her about how Copenhagen could better respect itself; the bewildering array of political parties putting signs up all over the city, and how rarely their actions match their words; her desire for children to grow up in the same Copenhagen she did; the evolution of Amager, also known as “the Shit Island”, and what gentrification looks like elsewhere in the city; the scourge of Joe and the Juice; and her continuing search outward for more “traces of life” in Copenhagen.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

I often ask Angeleno acquaintances between forty and fifty years of age if they really, at one time in their lives, thought of Westwood as a place. Most reply that, especially during the early 1980s, they not only thought of Westwood as a place, but as the place. More recent arrivals such as myself have trouble believing these stories of Westwood nightlife, especially given the bad press the neighborhood has endured over the past couple of decades: too much a clash of elements, say architectural observers; too far-flung and emblematic of the west side’s backward resistance to rapid transit, say urbanists; too hard to park there, say longtime Los Angeles residents and visiting shoppers. Other than the Hammer Museum, which plays the role of sole attraction for as many people as does the Annenberg Center for Photography inCentury City, the area seems, at present and from a distance, to have mostly strikes against it. Hence that question I put to those here long enough to have experienced its heyday; the very phrase “Hey, let’s go to Westwood on Friday” rings, to me, more than a little false.

Whenever I make my own way over there, I do find a nice enough place to pass an afternoon, but so the commonly agreed-upon sentiment that it used to enjoy a great deal more vitality than it does now makes sense. Fewer agree on what, exactly, drained it away. Writing on Old Pasadena, I mentioned UCLA parking theorist Donald Shoup’s research into the parking policy of that neighborhood, which seemingly revitalized itself through productive use of parking meter revenues; versus that of Westwood, which involved reducing parking rates instead and hoping for the best. This resulted in little more than a hardening of the place’s already-earned reputation of unparkability. That, in and of itself, may say little against Westwood — you’d have an even tougher time parking in most of the world’s most exciting cities, by their very nature — unless, of course, like a fair few of those who would converge there in its era as “the place,” you had to come in by car from ten, twenty, thirty miles away.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Monday, November 25, 2013

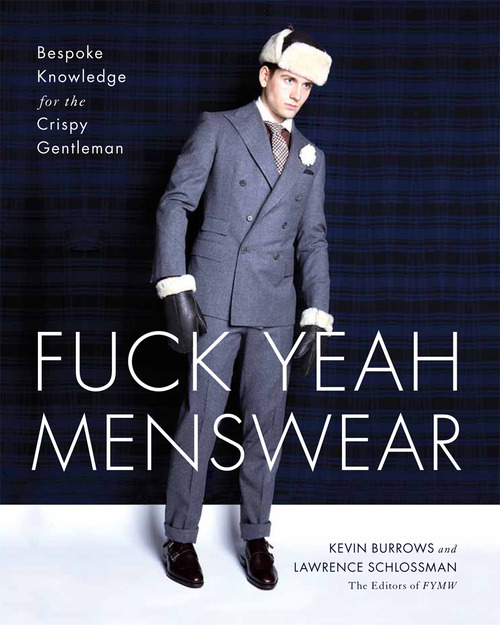

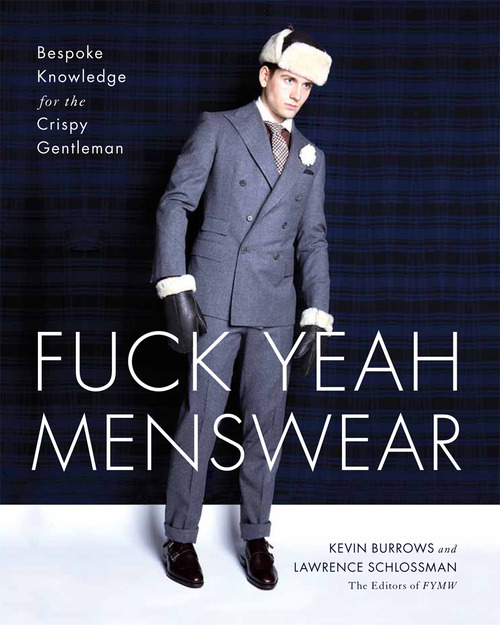

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on their now-still Tumblr blog of the same name, though with one remarkable difference: this book embraces, even as it ridicules, the internet age and what it has done to menswear culture. Here we have a book that startles by simply existing on paper, so thoroughly has it embedded itself in and so instinctively does it reference its grand coterie of style bloggers, style forum posters, and style eBay buyer-sellers. Its authors might also identify a great many others in the crowd around them: bluehands, dashmunchers, herbs, OGs, photogs, plebes, and Uggs (not, needless to say, to indicate the questionable boots, but the questionable ladies wearing them).

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on their now-still Tumblr blog of the same name, though with one remarkable difference: this book embraces, even as it ridicules, the internet age and what it has done to menswear culture. Here we have a book that startles by simply existing on paper, so thoroughly has it embedded itself in and so instinctively does it reference its grand coterie of style bloggers, style forum posters, and style eBay buyer-sellers. Its authors might also identify a great many others in the crowd around them: bluehands, dashmunchers, herbs, OGs, photogs, plebes, and Uggs (not, needless to say, to indicate the questionable boots, but the questionable ladies wearing them).

All those terms come straight out of the glossary near the end of Fuck Yeah Menswear (which comes just before an elaborate pastiche of the kind of Japanese magazines for which I admittedly pay $18 a pop). Unlike similar addenda in most men’s style manuals, it functions less as a utility than as a piece of entertainment in itself, and I count it as only one of a host of unusual, comedy-driven choices the book makes. These begin with the very premise that made Burrows and Schlossman’s presence on style-saturated Tumblr so notable in the first place: to derive line after line of satirical lyrics from the photographs of highly dressed men out and about in such now-endless digital supply. A thin young fellow on an East Village street corner, for instance, all peaked-lapel navy blazer and rolled-up denim, his aviators and heritage-design bicycle gleaming, looking to get snapped by a bigtime blogger: “This is the spot. I’m sure of it. I’m up next. Finally. Finna style. Finna get shot. Call me Fitty. Send a text to Mom.”

Read the whole essay at Put This On.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of the movement of the same name, which aims to make the Danish not just the “happiest” people, but the friendliest as well. They discuss just what it feels like to bear the label of “happiest” and whether “most content” might not suit the country better; the difference in impact of the word “fucking,” especially in a book title, between Denmark and the States; the seemingly inward-turned people foreigners feel as if they encounter when they first visit Denmark; his TEDx Copenhagen talk about his realization that he acted less friendly when speaking Danish than he did when speaking English; “negative politeness” versus “positive politeness”; the importance of internalizing a culture in order to speak its language; how the Danish once had to meet few non-Danes, and how they can still feel the effects of that in American questions like “How you doin’?”; the process and impact of “baking a little meaning” into each social encounter; his tendency to act, when in the Danish countryside, in a way that makes his wife call him “homo jovialis”; how compliments and other acts of friendliness require not just honesty but creativity and surprise for maximum effectiveness; the origins of the Fucking Flink movement, and the stunts he has pulled off with it, such as giving out positive parking tickets; the similar misery of commenting on the internet, driving in traffic on the highway, and staying too embedded in your own culture; the Avatar handshake, and what we can learn from the accompanying greeting of “I see you”; how best to address the needs we have when we get to the top of the Maslow Pyramid; the need to use not just what’s between our ears, but what’s between us; and how this all relates to the 4,000 years’ worth of city building coming very soon.

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of the movement of the same name, which aims to make the Danish not just the “happiest” people, but the friendliest as well. They discuss just what it feels like to bear the label of “happiest” and whether “most content” might not suit the country better; the difference in impact of the word “fucking,” especially in a book title, between Denmark and the States; the seemingly inward-turned people foreigners feel as if they encounter when they first visit Denmark; his TEDx Copenhagen talk about his realization that he acted less friendly when speaking Danish than he did when speaking English; “negative politeness” versus “positive politeness”; the importance of internalizing a culture in order to speak its language; how the Danish once had to meet few non-Danes, and how they can still feel the effects of that in American questions like “How you doin’?”; the process and impact of “baking a little meaning” into each social encounter; his tendency to act, when in the Danish countryside, in a way that makes his wife call him “homo jovialis”; how compliments and other acts of friendliness require not just honesty but creativity and surprise for maximum effectiveness; the origins of the Fucking Flink movement, and the stunts he has pulled off with it, such as giving out positive parking tickets; the similar misery of commenting on the internet, driving in traffic on the highway, and staying too embedded in your own culture; the Avatar handshake, and what we can learn from the accompanying greeting of “I see you”; how best to address the needs we have when we get to the top of the Maslow Pyramid; the need to use not just what’s between our ears, but what’s between us; and how this all relates to the 4,000 years’ worth of city building coming very soon.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast I have a conversation with Jerry Stahl, author of books like Permanent Midnight and I, Fatty as well as two new novels just this year, Bad Sex on Speed and Happy Mutant Baby Pills. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down in the Copenhagen offices of

Colin Marshall sits down in the Copenhagen offices of

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on  Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of