Last time I visited Mexico City, I recorded a single interview for The Marketplace of Ideas and spent the rest of the time exploring and hanging out (mostly with Japanese people). This year I had a whole slate of Notebook on Cities and Culture conversations to record, not much time in which to do it, and a truly nasty sore throat. But I also had a fairly nice apartment just off a park in Colonia Roma, my lady with me, and the ever-more-certain knowledge that, what with the seasonal change in weather, even genuine Chilangos felt the dolor in their own gargantas. The trip offered a brief opportunity, in one of my favorite cities in the world, to test a theory I’ve developed: if you want to get to know a place quickly, make a podcast where you not only interview people living and working there, but meet them at locations of their choosing, and ask them for recommendations of what to do on your off hours. (You’ll have to call your podcast something else.)

By contrast to Japan, I meet very few Brits in Mexico. (Aside from the aforementioned Japanese, every expat I know there comes from the United States.) How pale Londoners must go — how much paler, I mean — upon taking their first taxi trip in el D.F. The driving itself raises no particular hairs; though cars do go wherever they want, whenever they want, every driver on the road understands and accepts this. Every cabbie I’ve hired in Mexico has displayed great politeness, reasonable friendliness, and no inclination toward kidnapping, none have passed the Knowledge. I’ve had to get out of one taxi and find another after the first driver finally admitted to not knowing of my destination. This time, in from the airport, I handed our driver a map with our rental highlighted, but he still kept pulling over to ask fruit-sellers the direction of the street — and most of them didn’t know, either. Yet we ultimately found out way there, just as most of Mexico City’s systems, in their ad hoc, improvisational, theoretically unworkable ways, eventually produce something like the desired ends. (Or maybe they just need cheaper dashboard GPS systems.)

In healthier moments, I savored the elements that made me come back to Mexico City, and will make me come back again: delicious things to eat sold on half the sidewalks in town, the now-aesthetically retro Metro, Cuban ice cream without the promise to buy, scary dead yet somehow living buildings like Condominio Insurgentes. In fact, I couldn’t resist bringing up the Condominio Insurgentes in an interview, though the fact that I was talking with a couple of architect-urbanists made it fair game. They agreed to its reflection of something important yet difficult to define about the capital’s often wonky urban landscape. Conversations like these tend to make me forget that I have the chills, can barely swallow, or need desperately to slink off and collapse. Consider credence lent to the Noël Coward pronouncement I quote more frequently all the time: “Work is more fun than fun.” Helps if your work involves exploring world cities, talking, and making friends. And it would help more if my own work involved a bit more proper, actual-lifestyle-supporting money. But you’ll hear no complaints from me.

Despite enjoying the company of Japanese people in Mexico City, I’ve never braved its Japanese food. Serious eaters tell me that world-class Japanese eateries have opened there in the past decade, but casual eaters still report sushi filled with cream cheese and topped with thick dollops of hot sauce and mayonnaise. You’ll know I’ve attained supreme world-weariness when you catch me at one of those waterless street tents under the beating sun advertising “SUSHI RECIEN HECHO.” I have nothing against the hybridization of cuisines — in fact, few processes fascinate me more — but certain food traditions have unhappy encounters with Mexico. (Not that I consider American-style sushi rolls, leaden with every possible flavor and texture then fried whole, a point of national pride.) One foreign food writer described to me what he called “Mexican Chinese food”: greasy fried rice, greasier chow mein, glops of orange sweet-and-sour sauce, all presented in exposed steam trays. We have those in Los Angeles too, I told him, which got him thinking about standard American Chinese food: chop suey, General Tso’s, and what have you. No, no, I corrected; even in Koreatown, we’ve also got Chinese joints only for Mexicans.

Needless to say, this stretch in Mexico City soon found Jae and I making a beeline to the Zona Rosa, which has a tiny Koreatown of its own. Gorging ourselves on barbecue and makgeolli at Nadefo, a place on Liverpool recommended by my past interviewee David Lida, we reflected, fully, on our great good fortune. Aside from the Mexican waiters (and probably most of the chefs), I looked around at the end of the meal and found myself seemingly the only non-Korean in the room — never a bad omen, if you seek to eat well. Close to 10,000 of them live in or near the neighborhood (often described, question-dodgingly, as working in “import-export”), which serves them not just with restaurants, but internet cafés and noraebang. Then, from the corner, we heard the familiarly clipped syllables of the Japanese language and realized that Nadefo draws a trickle of nihonjin as well. That explains all the posters and table cards advertising Calpis, “el Sabor Original de Japón.”

As a Spanish-language media capital, Mexico City produces a great deal of television meant to appeal broadly across Latin America. However, curiously little of it found its way to our apartment television. Jae tuned the set to, and left it on, something called Classic Arts Showcase, a channel that screens nothing but a loop of short clips from theater, dance, and symphonic performances. This started to look to me, as I sat recovering from the sore throat and various other minor ailments, like a near-ideal realization of an idea I had a few years back for “ambient television.” Some friends suggested I launch the concept as a YouTube channel, but it struck me as the sort of media that doesn’t work if you have to actively seek it out; it needs to present itself as a kind of default. (The 21st century has yet, I think, to grasp the importance of this distinction.) Just as I began wondering why Mexico had gotten to into 20th-century European culture, a message appeared announcing Classic Arts Showcase’s address as just up the road in Burbank. If I had an “Industry” day job, I would surely work at a place like that. Assuming they have employees.

If you pursue the craft of interviewing yourself and need a challenge to take you to the next level, I recommend conducting an interview in a language other than your native one. I mean, I’ve personally never tried it; in Spanish, I’d still struggle to process each response in a timely fashion, and as for Korean and Japanese, oh, the humanity. But to more easily get at least to the level below that, I recommend conducting an interview in a language other than your guest’s native one. Also unlike my sessions Japan, most of my guests in Mexico actually came from Mexico, several having been born and raised right there in el D.F. I came to find out that, especially among what you might call the literary classes, sending one’s kids to multilingual schools, or even exclusively English schools, has become accepted practice. (“Why don’t they do this in the States?” asked one interviewee. Shrug.) Grown, they wind up with English anywhere between accented but impressively functional and near-native sounding. Still, talking to them as an interviewer, you crank up your clarity, succinctness, and broadness (presumably of the least stupid kind) several notches, and, in my experience, sometimes draw out more expansive answers in so doing.

For myself, I just feel relieved to have passed the crucible of the telephone. As any language-learner knows, if the task of understanding and making yourself understood in person intimidates, the task of understanding and making yourself understood over the phone intimidates deeply. Hence my former practice of having hotels and restaurants call cabs for me; I needed to get to a certain place by a certain time, and didn’t trust in my own linguistic ability to guarantee that would happen. Yet getting ready to catch our flight back to Los Angeles, I rung up a cab company and ordered a ride without thinking twice about it. I hung up the phone — or rather, had it disconnected late in the call by patchy coverage — estimating the chances of the cab’s arrival at a generous 50-50, but it proceeded to arrive right in front of the door, where I had haltingly specified, bang on time, no kidnapping attempted. Will I get so lucky on my next trip to Asia?

[Previous diaries: Portland 2013, Kansai 2012, Seattle 2012, Portland 2012, San Francisco 2012, Mexico City 2011]

Colin Marshall sits down in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma with Diego Rabasa, co-founder of

Colin Marshall sits down in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma with Diego Rabasa, co-founder of

Colin Marshall sits down in Silver Lake, Los Angeles with Vincent Brook, teacher at UCLA, USC, Cal State Los Angeles, and Pierce College, and author of books on Jewish émigré directors and the Jewish sitcom as well as the new Land of Smoke and Mirrors: A Cultural History of Los Angeles. They discuss the difference between Los Angeles obsession and Los Angeles chauvinism; his time in Berkeley, when Los Angeles became the enemy; the Christopher Dorner incident and the old racial wounds it has re-opened; Gangster Squad and the cinematic abuse of Los Angeles history; the city’s tendency to repurpose rhetoric about it, no matter how negative, and Reyner Banham’s role in that; Los Angeles as Sodom, Gomorrah, and whipping boy; what the German word Stadtbild means, and how Los Angeles lacks it; the great power ascribed to the city by its criticism; whether or not we only use twenty percent of brains, or of cities; hidden places, including but not limited to Barnsdall Park; the work Los Angeles requires from you to master it, and whether that counts as a desirable quality; how technology enables you to watch Sunset Boulevard as you cruise down Sunset Boulevard; Watts Towers as the key to Los Angeles; the city’s far-flung museums, and their 21st-century tendency to roll large objects through the streets; how he came to teach a Rhetoric of Los Angeles class, and what his students have taught him; the truth of most local legends, even when contradictory; and how best to see the Los Angeles palimpsest.

Colin Marshall sits down in Silver Lake, Los Angeles with Vincent Brook, teacher at UCLA, USC, Cal State Los Angeles, and Pierce College, and author of books on Jewish émigré directors and the Jewish sitcom as well as the new Land of Smoke and Mirrors: A Cultural History of Los Angeles. They discuss the difference between Los Angeles obsession and Los Angeles chauvinism; his time in Berkeley, when Los Angeles became the enemy; the Christopher Dorner incident and the old racial wounds it has re-opened; Gangster Squad and the cinematic abuse of Los Angeles history; the city’s tendency to repurpose rhetoric about it, no matter how negative, and Reyner Banham’s role in that; Los Angeles as Sodom, Gomorrah, and whipping boy; what the German word Stadtbild means, and how Los Angeles lacks it; the great power ascribed to the city by its criticism; whether or not we only use twenty percent of brains, or of cities; hidden places, including but not limited to Barnsdall Park; the work Los Angeles requires from you to master it, and whether that counts as a desirable quality; how technology enables you to watch Sunset Boulevard as you cruise down Sunset Boulevard; Watts Towers as the key to Los Angeles; the city’s far-flung museums, and their 21st-century tendency to roll large objects through the streets; how he came to teach a Rhetoric of Los Angeles class, and what his students have taught him; the truth of most local legends, even when contradictory; and how best to see the Los Angeles palimpsest.

Colin Marshall sits down in Westwood, Los Angeles with

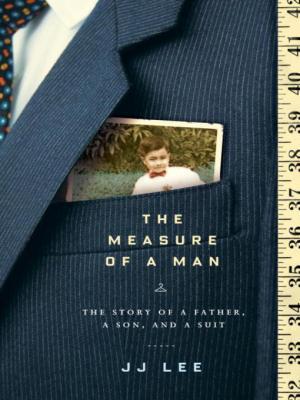

Colin Marshall sits down in Westwood, Los Angeles with  The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit presents us with an unusual form: the menswear memoir. It offers not the story of a life in the male garment trade, nor of a long career spent cutting and sewing. Nevertheless, it does contain a fair bit of material — pun only faintly intended — about developing a discerning sartorial eye, and about learning how to stitch a proper seam. Chinese-Canadian author JJ Lee made his name as a style writer and radio broadcaster, and only then, in his late thirties, did he begin studying at the feet of a master tailor. This in itself could make for a knocked-off entertainment freighted with a deadening subtitle like How a Mid-Life Apprenticeship Taught Me Everything I Needed to Know About Life, Love, and Lapels. But Lee elevates his work beyond such fluff by braiding in two other narratives: a history of the modern tailored suit, and the quick rise and prolonged, agonizing fall of his once well-turned out, aspirational, driven young father.

The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit presents us with an unusual form: the menswear memoir. It offers not the story of a life in the male garment trade, nor of a long career spent cutting and sewing. Nevertheless, it does contain a fair bit of material — pun only faintly intended — about developing a discerning sartorial eye, and about learning how to stitch a proper seam. Chinese-Canadian author JJ Lee made his name as a style writer and radio broadcaster, and only then, in his late thirties, did he begin studying at the feet of a master tailor. This in itself could make for a knocked-off entertainment freighted with a deadening subtitle like How a Mid-Life Apprenticeship Taught Me Everything I Needed to Know About Life, Love, and Lapels. But Lee elevates his work beyond such fluff by braiding in two other narratives: a history of the modern tailored suit, and the quick rise and prolonged, agonizing fall of his once well-turned out, aspirational, driven young father. Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with Clive Piercy, founder and principal of design studio

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with Clive Piercy, founder and principal of design studio