“When I came to, it was in a cloud of disbelief mixed with the stale taste of morning breath,” says Juniper Song, narrator and protagonist of “Follow Her Home”, Steph Cha’s 21st-century update on the Los Angeles noir novel. “I groaned and lay still with my eyes shut tight. As far as I could tell, I had been sapped.” An underemployed twentysomething dropped into the role of a modern-day Philip Marlowe, Song ends the second chapter already chloroformed by a menacing, sharp-suited thug. Yet when she awakes, she does so in the morning light, dumped in a decidedly un-noirish setting: “The geometric head of a Koo Koo Roo chicken winked down at me from behind. Someone had seen fit to cart me unconscious to Larchmont, on the Beverly end.” This branch of the chicken chain, in what I think of as the center of Larchmont Village, has since become a branch of the burrito chain Chipotle. Which, I wonder, would Raymond Chandler have given more of a stink eye?

Not that it matters now. The hybrid age in which we live permits nothing so straightforward as a Chandler noir, least of all in Los Angeles. Cha’s book merges the sensibility of the subgenre through which Marlowe slunk with the modern perspective of the Korean-American identity novel, and I could think of few settings more suitable, even for such a minor scene, than Larchmont Village, in part because so much of its shape appears to date from Chandler’s day. Had Song looked just beyond the Koo Koo Roo, she’d have seen the Larchmont Medical Building, the neighborhood’s not-particularly-tall tallest structure and exactly what an Angeleno of sixty years ago must have envisioned when they thought of a trip to the hospital. On much of the rest of Larchmont Boulevard, you see one- and two-story houses, the likes of which Marlowe would have cruised past on a hunch, squinting with suspicion, in the middle of the night. But look closer and you find that they, too, offer medical services, especially of the oral variety, containing offices of dentists, orthodontists, and even something called a prosthodontist.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with JJ Lee, menswear writer, broadcaster, and author of The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit. They discuss where to buy pocket squares in Vancouver (and whether to just have your kids make some); what to wear during the city’s “false start summer”; his own uses of color, and his gradual approach toward “weird clothes”; our coming age of wide-open, postmodern suit-wearing, a recovery from men getting stupid about dressing in the sixties and seventies; his own early dislike of suits, when they to him represented all that went wrong in society; his father’s quick rise, painful fall, and the undiagnosed, self-medicated depression that laid under it; his realization that people are highly aesthetic beings, always creating aesthetic moments; the adoption of tragic versus comic narratives, and which one led his father to stop dressing well; the way precision has replaced instinct for well-dressed men; Montreal and its status as Canada’s style capital; his favorable impression of Toronto’s dress, textbook though it may be; Vancouver’s athleticism-influenced casualness and its limitations; how he starts conversations with clothes, even in New York; the lie behind the idea of “truth” in dress; how men now wear suits, but often defensively, out of fear; the decline of Chinatown tailoring culture; the way men today don’t quite know how to be in a tailor shop, never having had that sort of interaction before; and his current project of essays on fatherhood, and the importance of leaving a legacy of ideas for his sons.

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with JJ Lee, menswear writer, broadcaster, and author of The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit. They discuss where to buy pocket squares in Vancouver (and whether to just have your kids make some); what to wear during the city’s “false start summer”; his own uses of color, and his gradual approach toward “weird clothes”; our coming age of wide-open, postmodern suit-wearing, a recovery from men getting stupid about dressing in the sixties and seventies; his own early dislike of suits, when they to him represented all that went wrong in society; his father’s quick rise, painful fall, and the undiagnosed, self-medicated depression that laid under it; his realization that people are highly aesthetic beings, always creating aesthetic moments; the adoption of tragic versus comic narratives, and which one led his father to stop dressing well; the way precision has replaced instinct for well-dressed men; Montreal and its status as Canada’s style capital; his favorable impression of Toronto’s dress, textbook though it may be; Vancouver’s athleticism-influenced casualness and its limitations; how he starts conversations with clothes, even in New York; the lie behind the idea of “truth” in dress; how men now wear suits, but often defensively, out of fear; the decline of Chinatown tailoring culture; the way men today don’t quite know how to be in a tailor shop, never having had that sort of interaction before; and his current project of essays on fatherhood, and the importance of leaving a legacy of ideas for his sons.

Download the interview from Notebook on Cities and Culture’s feed or on iTunes.

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast, I have a conversation Steph Cha, author of Follow Her Home, a new Los Angeles noir novel which puts an underemployed Korean-American twentysomething into the role of a modern-day Philip Marlowe. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with Paul Delany, professor of English at Simon Fraser University, editor of the reader Vancouver: Representing the Postmodern City, and author of the article “Vancouver: Graveyard of Ambition?” They discuss whether it makes sense to talk about a “postmodern” city in 2013; the influence of Douglas Coupland, William Gibson, and Jeff Wall; Vancouver’s future-oriented open-endedness; his path to Vancouver from England via the United States and specifically a crumbling New York; the state of Vancouver in 1970, when he arrived; how the West End became dense in the fifties, and how Yaletown evolved; English literature’s interest in the phenomenon of the modern city, and his own; the city as a nexus of fascinations; his disappointment in Vancouver’s architectural development and its lack of internationalism, save for buildings like the downtown library, the unofficial campus for the city’s many foreign language students; all the condo towers as Ballardian “prisons with the locks on the inside”; Microsoft’s aborted entry into Vancouver’s suburbs and its subsequent relocation to downtown; what led him to ask whether Vancouver made for a graveyard of ambition; the importance of getting outside Vancouver, and regularly; the lack of a fruitful intellectual model to replace postmodernism as a means of viewing Vancouver; and how the city’s large and growing Asian presence prepares it for the future.

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with Paul Delany, professor of English at Simon Fraser University, editor of the reader Vancouver: Representing the Postmodern City, and author of the article “Vancouver: Graveyard of Ambition?” They discuss whether it makes sense to talk about a “postmodern” city in 2013; the influence of Douglas Coupland, William Gibson, and Jeff Wall; Vancouver’s future-oriented open-endedness; his path to Vancouver from England via the United States and specifically a crumbling New York; the state of Vancouver in 1970, when he arrived; how the West End became dense in the fifties, and how Yaletown evolved; English literature’s interest in the phenomenon of the modern city, and his own; the city as a nexus of fascinations; his disappointment in Vancouver’s architectural development and its lack of internationalism, save for buildings like the downtown library, the unofficial campus for the city’s many foreign language students; all the condo towers as Ballardian “prisons with the locks on the inside”; Microsoft’s aborted entry into Vancouver’s suburbs and its subsequent relocation to downtown; what led him to ask whether Vancouver made for a graveyard of ambition; the importance of getting outside Vancouver, and regularly; the lack of a fruitful intellectual model to replace postmodernism as a means of viewing Vancouver; and how the city’s large and growing Asian presence prepares it for the future.

Download the interview from Notebook on Cities and Culture’s feed or on iTunes.

“Please stand clear. The doors are closing.”

“That’s right! The doors are closing — closing on your chance for salvation! And if you refuse to accept your lord and savior, you’ll find yourself behind those closed doors! Behind them for alleternity!”

The preacher went on, instinctively weaving each of the loudspeaker’s announcements into the morning’s forceful sermon. He wore a brown three-piece suit, not likely bespoke; his every gesticulation, and he made many, sent flying the extra fabric at his wrists and ankles. But what he lacked in tailoring, he made up in his distinctively both wild- and dead-eyed passion. The microphone he held to his mouth looked connected to nothing, yet his voice boomed as if amplified. Boomed through the whole car of the train, that is, undeterred even as my fellow passengers actively ignored it. I don’t see or hear this sort of thing every time I ride the Blue Line, not that it surprised me when I did.

Writing “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies” in the early seventies, Reyner Banham speculated about what form of transit would one day replace the freeways. “A rapid-rail system is the oldest candidate for the succession,” he wrote, “but nothing has happened so far. The core of the problem, I suspect, is that when the socially necessary branch has been built, to Watts, and the profitable branch, along Wilshire, little more will be done and most Angelenos will be an average of fifteen miles from a rapid-transit station.” This exemplifies Banham’s still-fascinating half-prescience: 22 years after the book appeared, the first stations of that “commercially necessary” Wilshire branch — the Purple Line I rode to the downtown coffee shop where I write these words — would open. Just a few years before that, Los Angeles’ long-awaited modern “rapid-rail” system began its operation with the “socially necessary” one, the Blue Line. Despite recent years’ glimmers of hope for extension, some riders have given up hope of ever riding a Purple Line train all the way under Wilshire Boulevard, but even upon its opening the Blue Line ran from downtown not just to Watts but well past it, all the way to Long Beach.

Read the whole thong at KCET Departures.

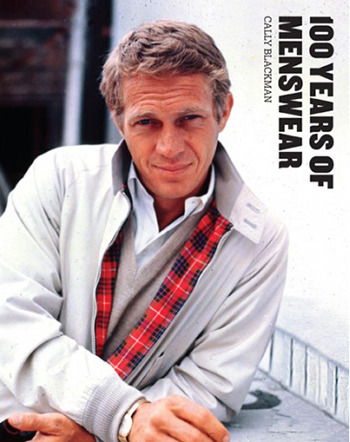

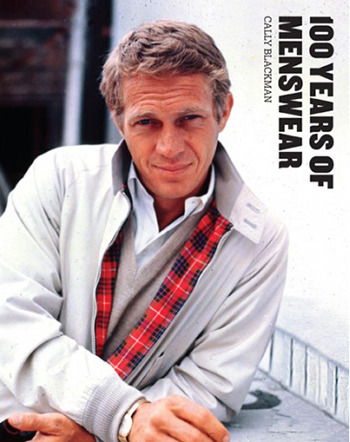

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

Even for quite a few of those rebels and peacocks, the most suitable form of dress remains, yes, the suit. “The three-piece suit, introduced and formalized in the late seventeenth century, has prospered for nearly 350 years because of its unique capacity for nuance and variation,” Blackman writes in the introduction. “To adapt a phrase from Le Corbusier, the suit is a machine for living in, close-fitting but comfortable armor, constantly revised and reinvented to be, literally, well-suited for modern daily life.” Yet twentieth-century menswear history tells, in large part, the story of the suit-wearing’s decline, which went especially precipitous in the late sixties. The pages of 100 Years of Menswear offer suits aplenty, both photographed and illustrated, in settings from the street to the workplace to (in a bizarre 1937 Esquire spread) the ski slopes, but they ultimately prioritize the diversity that the decades would let emerge: we see plus fours and pushed-up Miami Vice sleeves, tennis whites and motorcycle gear, Beatle boots and Nehru jackets – all, I suppose, the components of machines for living, albeit very different ways of doing it.

Read the whole thing at Put This On.

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast, I have a conversation Nathaniel Rich, fellow cityphile and author of San Francisco Noir, The Mayor’s Tongue, and the new Odds Against Tomorrow. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

DESPITE EXPORTING FOOD, film, advanced gadgetry, and dance music with unprecedented fervor and pride, South Korea has still produced curiously little in the way of an international literature. As Japan rose from the aftermath of the Second World War, so did vital men of letters like Kobo Abe, Oe Kenzaburo, and Yukio Mishima — names discussed in the West to this day. Japanese women of letters, a thread of unusual strength and length for an East Asian culture, running from Lady Murasaki and The Tale of Genji in the 11th century, continues through Yoko Ogawa and Banana Yoshimoto today. Haruki Murakami rose from the 1980s — the bubble era when fear of the Rising Sun’s apparent wealth and drive reached its apex — and would become the most globally appealing novelist alive, which he remains even today, when observers describe his country as well over a decade on the skids.

DESPITE EXPORTING FOOD, film, advanced gadgetry, and dance music with unprecedented fervor and pride, South Korea has still produced curiously little in the way of an international literature. As Japan rose from the aftermath of the Second World War, so did vital men of letters like Kobo Abe, Oe Kenzaburo, and Yukio Mishima — names discussed in the West to this day. Japanese women of letters, a thread of unusual strength and length for an East Asian culture, running from Lady Murasaki and The Tale of Genji in the 11th century, continues through Yoko Ogawa and Banana Yoshimoto today. Haruki Murakami rose from the 1980s — the bubble era when fear of the Rising Sun’s apparent wealth and drive reached its apex — and would become the most globally appealing novelist alive, which he remains even today, when observers describe his country as well over a decade on the skids.

Now turned outward as far as Japan has often turned inward, South Korea draws enthusiasts from all over the world. But pity the literarily inclined Koreaphile, filled with high hopes and accustomed by Western fiction to at least a thin layer of allegorical padding, for he usually winds up mired in nakedly melodramatic, discomfitingly direct meditations on national suffering in general, and the separation of North from South in particular. One period of national suffering stands out: the years 1910 to 1945, when the Korean Peninsula endured, at the hands of the Japanese military, something between a suppression and an erasure of its cultural identity. Generations of South Korean writers look past that era of occupation with difficulty, and they struggle harder still to find subjects beyond their land’s subsequent split into two.

Read the whole thing at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with Leslie Helm, former Tokyo correspondent for Business Week and the Los Angeles Times, editor of Seattle Business, and author of Yokohama Yankee: My Family’s Five Generations as Outsiders in Japan. They discuss the Asia connections of Los Angeles and Seattle; Japan’s changing place in the zeitgeist since when he covered their economic bubble; how he observed the West’s acceptance of Japan from his vantage as a quarter-Japanese yet Japanese-born “outsider”; how much of his family drama turns on the issue of how Japanese each member looks; the point of foreigner’s entry Yokohama was before it became considered an extension of Tokyo; how firm identities as foreigners helped members of his family’s older generations thrive in Japan; the new coolness of part-Japaneseness in this internationalist era; his frustration with the myth of Japanese difference and purity; what actually happened to Japan the economic powerhouse; the weakness of Japan’s craft-based strengths in a software-based economy; what the low level of English in Japan reveals about the country’s educational system; the fame his family accrued in the shipping business, and the bad reputation the company ultimately developed once sold; his kids, who look Japanese but grew up Western; the upside to the Japanese burden of obligations; to what extent Japan has realized it needs outsiders to keep the country going; what it means that Japan can burn through so many Prime Ministers in such a short time with no social disruption; the Shinto religion as Boy Scouts; how this book of family history became a painstakingly designed volume for the world to read; what America has, still, to learn from Japan; and which country seems more likely to overcome its worst tendencies.

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with Leslie Helm, former Tokyo correspondent for Business Week and the Los Angeles Times, editor of Seattle Business, and author of Yokohama Yankee: My Family’s Five Generations as Outsiders in Japan. They discuss the Asia connections of Los Angeles and Seattle; Japan’s changing place in the zeitgeist since when he covered their economic bubble; how he observed the West’s acceptance of Japan from his vantage as a quarter-Japanese yet Japanese-born “outsider”; how much of his family drama turns on the issue of how Japanese each member looks; the point of foreigner’s entry Yokohama was before it became considered an extension of Tokyo; how firm identities as foreigners helped members of his family’s older generations thrive in Japan; the new coolness of part-Japaneseness in this internationalist era; his frustration with the myth of Japanese difference and purity; what actually happened to Japan the economic powerhouse; the weakness of Japan’s craft-based strengths in a software-based economy; what the low level of English in Japan reveals about the country’s educational system; the fame his family accrued in the shipping business, and the bad reputation the company ultimately developed once sold; his kids, who look Japanese but grew up Western; the upside to the Japanese burden of obligations; to what extent Japan has realized it needs outsiders to keep the country going; what it means that Japan can burn through so many Prime Ministers in such a short time with no social disruption; the Shinto religion as Boy Scouts; how this book of family history became a painstakingly designed volume for the world to read; what America has, still, to learn from Japan; and which country seems more likely to overcome its worst tendencies.

Download the interview from Notebook on Cities and Culture’s feed or on iTunes.

Los Angeles once had a Seibu. Those who delve into the city’s history tend to obsess over some obscure happening from the past decade, the past century, the past two centuries. My own transfixing blip appeared just over half a century ago and disappeared soon after. “Even in Los Angeles — the city of gala premières for everything from Hollywood spectaculars to hamburger stands — the ‘grand opening’ last week of the U.S.’s first big Japanese-owned department store created quite a splash,” reported Time magazine on March 23, 1962. “Within 15 minutes after Seibu of Los Angeles unlocked its door, 5,000 shoppers were inside, women were fainting, policemen had to bar all entrances to slow down the rush and traffic was backed up for four blocks along Wilshire Boulevard.” But just two years later, America’s only Seibu, purveyor of the “oishii seikatsu” — “sweet life,” as I’d translate it — gave way to the probably more practical but crushingly less exotic Ohrbach’s. It shut down twenty years before I was born, but I still find myself thinking about the old Seibu whenever I walk by its location at the end of the Miracle Mile.

Though it gives me time and space to reflect on Japanese department stores of bygone days, traversing this stretch of Wilshire Boulevard on foot does perhaps snub its historic spirit. First developed in the twenties by A.W. Ross, a bust of whom still stands at 5800 Wilshire, these blocks between Highland and Fairfax Avenue (which actually add up to a mile and a half) offered prewar shoppers an automobile-friendly alternative to downtown crowding. Ross’ idea, the improbable success of which qualified as the “Miracle,” enjoyed a few good decades of eating downtown’s lunch, as they say. But by the time Seibu set up shop, decline had already set in, and the Miracle Mile’s own lunch got eaten in turn by postwar America’s signature far-flung suburban malls. (You can read more about this process in Nathan Masters’ “How the Miracle Mile Got its Name“.) Today, as city-center shopping and living undergoes a renaissance, many of those distant commercial behemoths look depressingly worse for wear; how long before we see a country-wide wave of mall demolitions? And where does that leave a place like the Miracle Mile, optimized neither for motorists nor pedestrians?

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with

Colin Marshall sits down in Vancouver’s Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden with

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with

Colin Marshall sits down in Yaletown, Vancouver, British Columbia with

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

DESPITE EXPORTING FOOD, film, advanced gadgetry, and dance music with unprecedented fervor and pride, South Korea has still produced curiously little in the way of an international literature. As Japan rose from the aftermath of the Second World War, so did vital men of letters like Kobo Abe, Oe Kenzaburo, and Yukio Mishima — names discussed in the West to this day. Japanese women of letters, a thread of unusual strength and length for an East Asian culture, running from Lady Murasaki and The Tale of Genji in the 11th century, continues through Yoko Ogawa and Banana Yoshimoto today. Haruki Murakami rose from the 1980s — the bubble era when fear of the Rising Sun’s apparent wealth and drive reached its apex — and would become the most globally appealing novelist alive, which he remains even today, when observers describe his country as well over a decade on the skids.

DESPITE EXPORTING FOOD, film, advanced gadgetry, and dance music with unprecedented fervor and pride, South Korea has still produced curiously little in the way of an international literature. As Japan rose from the aftermath of the Second World War, so did vital men of letters like Kobo Abe, Oe Kenzaburo, and Yukio Mishima — names discussed in the West to this day. Japanese women of letters, a thread of unusual strength and length for an East Asian culture, running from Lady Murasaki and The Tale of Genji in the 11th century, continues through Yoko Ogawa and Banana Yoshimoto today. Haruki Murakami rose from the 1980s — the bubble era when fear of the Rising Sun’s apparent wealth and drive reached its apex — and would become the most globally appealing novelist alive, which he remains even today, when observers describe his country as well over a decade on the skids. Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with