Tuesday, December 3, 2013

I’ve taken my recent trips to and from Bunker Hill exclusively by stair, owing to the current shutdown of Angels Flight, the beloved funicular that, when operational, carries passengers up from Hill Street and back down again. It doesn’t go out of order often, but when it does it often stays that way for some time: a fatal 2001 accident put it out of commission for nearly eight years, and before that, in 1969, the redevelopment of Bunker Hill brought about its dismantling and subsequent storage for just under three decades. What kind of a city, this leads one to ask, struggles to keep even the world’s shortest railway — and one of its few icons, at that — in continuous operation? In my case, this question encourages the darkly methodical contemplation of Los Angeles’ other infuriating qualities, one after the other: its vast, often ridiculous distances; the shabbiness of so much of its built environment, mini-malls and otherwise; the barely explicable gaps in, and slowness of the rest of, its rapid transit system; the percentage of its surfaces covered by advertisements for movies whose distributors couldn’t pay me to watch.

But moments before I decide to pull up stakes, I turn around and behold a counterargument: Grand Central Market, the urban emporium that has, since 1917, provided downtown residents a place to buy their produce. More recently than that, it has provided them a place to buy a variety of moles, dried chiles, and herbal medicines. More recently than that, it has provided them a place to buy a quick office-worker’s lunch. More recently still, it has provided them a place to buy ten-dollar hamburgers, thirteen-dollar Cobb salads, and six-dollar soy lattes. At this particular moment, these almost parodic manifestations of gentrification — preparation of that six-dollar soy latte involves not actual soy milk, but “a special almond milk we make here” — coexist fascinatingly with what habitués sometimes call the “old” Grand Central Market, by which they mean Grand Central Market as a delivery system of cheap vegetables and even cheaper meals. China Cafe, the most prominent representative of this era, appears right up front, its neon signs advertising “CHOP SUEY” and “CHOW MEIN” visible as soon as you enter from Hill. Come at the right time, well before the families and tourists turn up, and on its stools, beneath its menu surely unchanged by the decades, you can still find a handful of old alcoholics huddled over morning trays of egg foo young.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with Classic Copenhagen blogger and photographer Sandra Høj. They discuss the city’s current enthusiasm for tree-cutting; the small things in Copenhagen that draw her eye, from pieces of street art to weird details on houses; how she started blogging in the wake of the Muhammad caricature crisis with an interest in disputing the global perception of Danes as living obliviously in a land of pastries and fairy tales; her mission to describe “the good, the bread, and the ugly” of Copenhagen; the Danish tendency to nag about problems; what time spent in “cozy” Amsterdam taught her about her “sexy” home city; what time spend in Paris taught her about how Copenhagen could better respect itself; the bewildering array of political parties putting signs up all over the city, and how rarely their actions match their words; her desire for children to grow up in the same Copenhagen she did; the evolution of Amager, also known as “the Shit Island”, and what gentrification looks like elsewhere in the city; the scourge of Joe and the Juice; and her continuing search outward for more “traces of life” in Copenhagen.

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with Classic Copenhagen blogger and photographer Sandra Høj. They discuss the city’s current enthusiasm for tree-cutting; the small things in Copenhagen that draw her eye, from pieces of street art to weird details on houses; how she started blogging in the wake of the Muhammad caricature crisis with an interest in disputing the global perception of Danes as living obliviously in a land of pastries and fairy tales; her mission to describe “the good, the bread, and the ugly” of Copenhagen; the Danish tendency to nag about problems; what time spent in “cozy” Amsterdam taught her about her “sexy” home city; what time spend in Paris taught her about how Copenhagen could better respect itself; the bewildering array of political parties putting signs up all over the city, and how rarely their actions match their words; her desire for children to grow up in the same Copenhagen she did; the evolution of Amager, also known as “the Shit Island”, and what gentrification looks like elsewhere in the city; the scourge of Joe and the Juice; and her continuing search outward for more “traces of life” in Copenhagen.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

I often ask Angeleno acquaintances between forty and fifty years of age if they really, at one time in their lives, thought of Westwood as a place. Most reply that, especially during the early 1980s, they not only thought of Westwood as a place, but as the place. More recent arrivals such as myself have trouble believing these stories of Westwood nightlife, especially given the bad press the neighborhood has endured over the past couple of decades: too much a clash of elements, say architectural observers; too far-flung and emblematic of the west side’s backward resistance to rapid transit, say urbanists; too hard to park there, say longtime Los Angeles residents and visiting shoppers. Other than the Hammer Museum, which plays the role of sole attraction for as many people as does the Annenberg Center for Photography inCentury City, the area seems, at present and from a distance, to have mostly strikes against it. Hence that question I put to those here long enough to have experienced its heyday; the very phrase “Hey, let’s go to Westwood on Friday” rings, to me, more than a little false.

Whenever I make my own way over there, I do find a nice enough place to pass an afternoon, but so the commonly agreed-upon sentiment that it used to enjoy a great deal more vitality than it does now makes sense. Fewer agree on what, exactly, drained it away. Writing on Old Pasadena, I mentioned UCLA parking theorist Donald Shoup’s research into the parking policy of that neighborhood, which seemingly revitalized itself through productive use of parking meter revenues; versus that of Westwood, which involved reducing parking rates instead and hoping for the best. This resulted in little more than a hardening of the place’s already-earned reputation of unparkability. That, in and of itself, may say little against Westwood — you’d have an even tougher time parking in most of the world’s most exciting cities, by their very nature — unless, of course, like a fair few of those who would converge there in its era as “the place,” you had to come in by car from ten, twenty, thirty miles away.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Monday, November 25, 2013

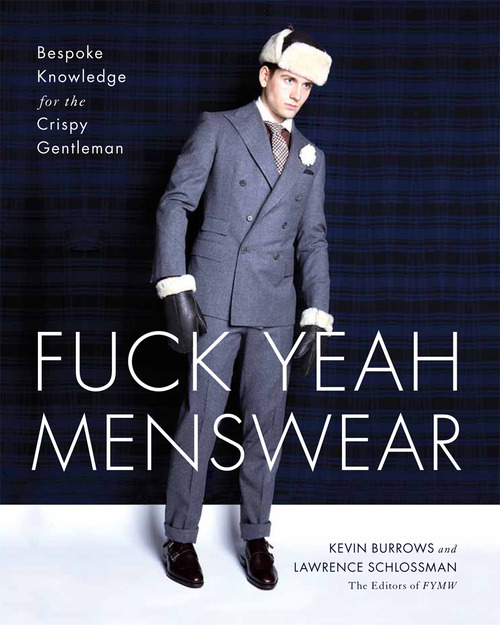

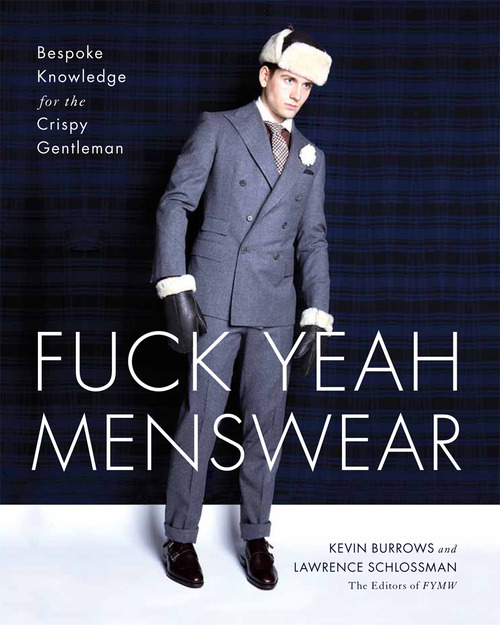

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on their now-still Tumblr blog of the same name, though with one remarkable difference: this book embraces, even as it ridicules, the internet age and what it has done to menswear culture. Here we have a book that startles by simply existing on paper, so thoroughly has it embedded itself in and so instinctively does it reference its grand coterie of style bloggers, style forum posters, and style eBay buyer-sellers. Its authors might also identify a great many others in the crowd around them: bluehands, dashmunchers, herbs, OGs, photogs, plebes, and Uggs (not, needless to say, to indicate the questionable boots, but the questionable ladies wearing them).

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on their now-still Tumblr blog of the same name, though with one remarkable difference: this book embraces, even as it ridicules, the internet age and what it has done to menswear culture. Here we have a book that startles by simply existing on paper, so thoroughly has it embedded itself in and so instinctively does it reference its grand coterie of style bloggers, style forum posters, and style eBay buyer-sellers. Its authors might also identify a great many others in the crowd around them: bluehands, dashmunchers, herbs, OGs, photogs, plebes, and Uggs (not, needless to say, to indicate the questionable boots, but the questionable ladies wearing them).

All those terms come straight out of the glossary near the end of Fuck Yeah Menswear (which comes just before an elaborate pastiche of the kind of Japanese magazines for which I admittedly pay $18 a pop). Unlike similar addenda in most men’s style manuals, it functions less as a utility than as a piece of entertainment in itself, and I count it as only one of a host of unusual, comedy-driven choices the book makes. These begin with the very premise that made Burrows and Schlossman’s presence on style-saturated Tumblr so notable in the first place: to derive line after line of satirical lyrics from the photographs of highly dressed men out and about in such now-endless digital supply. A thin young fellow on an East Village street corner, for instance, all peaked-lapel navy blazer and rolled-up denim, his aviators and heritage-design bicycle gleaming, looking to get snapped by a bigtime blogger: “This is the spot. I’m sure of it. I’m up next. Finally. Finna style. Finna get shot. Call me Fitty. Send a text to Mom.”

Read the whole essay at Put This On.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of the movement of the same name, which aims to make the Danish not just the “happiest” people, but the friendliest as well. They discuss just what it feels like to bear the label of “happiest” and whether “most content” might not suit the country better; the difference in impact of the word “fucking,” especially in a book title, between Denmark and the States; the seemingly inward-turned people foreigners feel as if they encounter when they first visit Denmark; his TEDx Copenhagen talk about his realization that he acted less friendly when speaking Danish than he did when speaking English; “negative politeness” versus “positive politeness”; the importance of internalizing a culture in order to speak its language; how the Danish once had to meet few non-Danes, and how they can still feel the effects of that in American questions like “How you doin’?”; the process and impact of “baking a little meaning” into each social encounter; his tendency to act, when in the Danish countryside, in a way that makes his wife call him “homo jovialis”; how compliments and other acts of friendliness require not just honesty but creativity and surprise for maximum effectiveness; the origins of the Fucking Flink movement, and the stunts he has pulled off with it, such as giving out positive parking tickets; the similar misery of commenting on the internet, driving in traffic on the highway, and staying too embedded in your own culture; the Avatar handshake, and what we can learn from the accompanying greeting of “I see you”; how best to address the needs we have when we get to the top of the Maslow Pyramid; the need to use not just what’s between our ears, but what’s between us; and how this all relates to the 4,000 years’ worth of city building coming very soon.

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of the movement of the same name, which aims to make the Danish not just the “happiest” people, but the friendliest as well. They discuss just what it feels like to bear the label of “happiest” and whether “most content” might not suit the country better; the difference in impact of the word “fucking,” especially in a book title, between Denmark and the States; the seemingly inward-turned people foreigners feel as if they encounter when they first visit Denmark; his TEDx Copenhagen talk about his realization that he acted less friendly when speaking Danish than he did when speaking English; “negative politeness” versus “positive politeness”; the importance of internalizing a culture in order to speak its language; how the Danish once had to meet few non-Danes, and how they can still feel the effects of that in American questions like “How you doin’?”; the process and impact of “baking a little meaning” into each social encounter; his tendency to act, when in the Danish countryside, in a way that makes his wife call him “homo jovialis”; how compliments and other acts of friendliness require not just honesty but creativity and surprise for maximum effectiveness; the origins of the Fucking Flink movement, and the stunts he has pulled off with it, such as giving out positive parking tickets; the similar misery of commenting on the internet, driving in traffic on the highway, and staying too embedded in your own culture; the Avatar handshake, and what we can learn from the accompanying greeting of “I see you”; how best to address the needs we have when we get to the top of the Maslow Pyramid; the need to use not just what’s between our ears, but what’s between us; and how this all relates to the 4,000 years’ worth of city building coming very soon.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast I have a conversation with Jerry Stahl, author of books like Permanent Midnight and I, Fatty as well as two new novels just this year, Bad Sex on Speed and Happy Mutant Baby Pills. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

How many degrees could possibly separate any given Angeleno from someone who lives, or has lived, in Park La Brea? The well-known, highly visible apartment complex, located just north of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, seems to bring forth an anecdote from just about everyone. At a Q&A session after a screening of his documentary “Los Angeles Plays Itself,” I heard filmmaker Thom Andersen mention having once moved there after regarding it for years as the most glamorous place imaginable. (He has since climbed what many Los Angeles architecture buffs would consider more than a rung or two up the glamor ladder, to a Rudolf Schindler house in Silver Lake.) A friend of mine told me about a girl he briefly dated years ago; as soon as he made it into her apartment, high in one of Park La Brea’s eighteen thirteen-story towers, he took one glance at her awful furniture and knew they would never work out. Another regularly gives tours there to Los Angeles-transferred professionals in need of living space. My own girlfriend also put in some time there, albeit as a little kid.

Everyone comes to Park La Brea for their own reasons; I, as a non-resident but regular visitor, have linguistic ones. In the course of my Korean language study, I met a Korean family who, impressed at my determination to practice their mother tongue — impressed, I assume, for the same reason Dr. Johnson regarded the proverbial upright-walking dog as impressive — they generously invited me to stop by their home each week for additional instruction in Korean language and culture. With the wife on sabbatical from her job teaching economics at a Seoul university, the family had decided to spend the time off in Los Angeles, moving into one of Park La Brea’s two-story garden apartments. The first time I tried to stop by, I promptly lost my way in the complex’s series of roundabouts and radiating diagonal paths. Luckily, I’d allowed time for just such a navigational struggle. Flying into LAX, I’d always taken note from above of Park La Brea’s geometry which, though precise and immediately recognizable, gave me a sense of trouble. I count myself lucky that I haven’t lived there yet and haven’t had to go through the nighttime ordeal of getting home drunk.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Friday, November 15, 2013

Colin Marshall sits down before a live audience at the New Urbanism Film Festival at Los Angeles’ ACME Theater with Tim Halbur, Director of Communications at the Congress for the New Urbanism, former Managing Editor at Planetizen, creator of the two-disc DVD set The Story of Sprawl, and author of the children’s urban planning book Where Things Are from Near to Far. They discuss the anti-Los Angeles indoctrination he received in San Francisco, and what that indoctrination might have had right; the two “nodes” of Hollywood and the beach that outsiders tend to recognize in Los Angeles, and why people claim to live here even when they live thirty miles away; why cities actually build for the car aren’t as often derided as “built for the car”; the hard-to-place unease we grew up with in the suburbs; his past producing museum audio tours, and how he would produce an audio tour of Los Angeles that navigates by subcultures; whether Los Angeles is too big, and what it means that we continually try to define and connect it all; what the Congress for the New Urbanism does, and how it addresses the way we once “carved out” our cities for parking lots and freeways; the Jetsonian vision of the future that carried us away after the Second World War; what Disneyland gets right about urbanism; the constant change that defines a living city, and San Francisco’s unhappy experience trying to halt it; the Beverly Hills 90210 model of denser-than-suburbia living he found in Los Angeles; his weekly commute to the CNU in Chicago, and what he learns from living in these two quite different cities at once; how he’d like to see Los Angeles change in the next ten years; how Eric Brightwell‘s neighborhood maps surprise people, and what that means for neighborhood awareness; and the importance of “theming” urban places.

Colin Marshall sits down before a live audience at the New Urbanism Film Festival at Los Angeles’ ACME Theater with Tim Halbur, Director of Communications at the Congress for the New Urbanism, former Managing Editor at Planetizen, creator of the two-disc DVD set The Story of Sprawl, and author of the children’s urban planning book Where Things Are from Near to Far. They discuss the anti-Los Angeles indoctrination he received in San Francisco, and what that indoctrination might have had right; the two “nodes” of Hollywood and the beach that outsiders tend to recognize in Los Angeles, and why people claim to live here even when they live thirty miles away; why cities actually build for the car aren’t as often derided as “built for the car”; the hard-to-place unease we grew up with in the suburbs; his past producing museum audio tours, and how he would produce an audio tour of Los Angeles that navigates by subcultures; whether Los Angeles is too big, and what it means that we continually try to define and connect it all; what the Congress for the New Urbanism does, and how it addresses the way we once “carved out” our cities for parking lots and freeways; the Jetsonian vision of the future that carried us away after the Second World War; what Disneyland gets right about urbanism; the constant change that defines a living city, and San Francisco’s unhappy experience trying to halt it; the Beverly Hills 90210 model of denser-than-suburbia living he found in Los Angeles; his weekly commute to the CNU in Chicago, and what he learns from living in these two quite different cities at once; how he’d like to see Los Angeles change in the next ten years; how Eric Brightwell‘s neighborhood maps surprise people, and what that means for neighborhood awareness; and the importance of “theming” urban places.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast I have a conversation with Michael Krikorian, longtime Los Angeles gang reporter and author of the new crime novel Southside. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

If we call the seaside Santa Monica, home of Third Street Promenade, one of Los Angeles’ major “satellite cities,” then we must also grant the title to Pasadena, which goes its own way in the opposite setting, under the San Gabriel mountains. Both incorporated in 1886, both boast populations around 100,000 (Santa Monica a few thousand lower, Pasadena a few thousand higher), and both have gained reputations for substantial, if not outlandish, wealth. Both independent municipalities have also, in their separate ways and positions — Santa Monica to the west, Pasadena to the northeast — maintained a psychological disconnection from, not to say a disdain for, the metropolis between them. In Robert Altman’s The Player, Tim Robbins’ movie-studio VP undergoes casual police questioning. “You’re putting me in a terrible position here,” he says, nervously. “I’d hate to get the wrong person arrested.” “Oh, please!” responds Whoopi Goldberg’s detective. “This is Pasadena. We do not arrest the wrong person. That’s L.A.!”

Still, residing in a place like Pasadena has never stopped anyone from, when it suits them, claiming to live in Los Angeles — it does, after all, lie within the eponymous county. It also, like Santa Monica, provides something of a pressure valve to those unaccustomed to the too-big city it borders: those bewildered and disoriented by Los Angeles proper can make a retreat there, a return to the more traditional look, feel, and form they can readily comprehend. Nowhere will they feel more at ease than in the original business district, almost without exception called Old Town Pasadena on the street, but now zealously branded, for whatever reason, as Old Pasadena. Concentrated in the blocks around Colorado Boulevard and Fair Oaks Avenue, this historic building-rich core — called, in promotional materials, “The Real Downtown,” — has in recent years reinvented itself as a walking-friendly shopping district, thick with all manner of buying opportunities. One often hears enthusiasm for Pasadena, and the satellite cities in its league, put in terms of the observation that “you have everything here,” a feeling the presence of zones like these no doubt fuels.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with

Colin Marshall sits down in Nørrebro with

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on

Whether published this century or the last, most men’s style books I pick up don’t present themselves as products of the internet age. This even holds for volumes that owe their very existence to the popularity of their authors’ blog, web series, Tumblr, what have you. So the process seems to have gone with Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman’s Fuck Yeah Menswear: Bespoke Knowledge for the Crispy Gentleman, the fruit of their labor on  Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of

Colin Marshall sits down in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro with Lars AP, author of the book Fucking Flink and founder of

Colin Marshall sits down before a live audience at the New Urbanism Film Festival at Los Angeles’ ACME Theater with Tim Halbur, Director of Communications at the

Colin Marshall sits down before a live audience at the New Urbanism Film Festival at Los Angeles’ ACME Theater with Tim Halbur, Director of Communications at the