Sunday, February 23, 2014

Vital stats:

Format: David Lee Roth’s “social-studies lectures by way of rock ‘n’ roll Babylon, at carnival-barker cadence”

Episode duration: 20-50m

Frequency: biweekly, with hiatuses

I found out about The Roth Show [RSS] [iTunes] from an in-depth profile of its host, yes, former and current Van Halen lead singer David Lee Roth. The article, Steve Kandell’s “David Lee Roth Will Not Go Quietly”, appeared on Buzzfeed, of all places, but I didn’t judge, I just marveled. Specifically, I marveled at Kandell’s description of Roth’s lack of furniture and possession of “a rack of Japanese katana swords,” his successful completion of an EMT program in New York and tactical medicine training in Southern California, his 600-pound ex-sumo wrestler language mentor, his apartment in Tokyo, his lifestyle “rich and weird and singular and driven by very particular and exotic enthusiasms ranging from mountain climbing to martial arts to tending to gunshot victims in the Bronx.”

Needless to say, Kandell’s mention of a Roth-helmed “sprawling one-man video series and podcast that aspires to do nothing less than tell the history of modern culture through the eyes of someone who has been everywhere, done everything, met everyone, and hired a couple of midgets to be his security detail along the way” raised my eyebrow. “It’s nothing more or less than David Lee Roth speaking for a half hour on, more or less, a single topic. Tattoos. FM and underground radio. The history and semiotics of pop videos by way of Picasso. A long-ago trip to New Guinea. His personal history with drinking and smoking. Slideshows from an unending vacation. The episodes are monologues, history lessons, personal taxonomy, but really, mostly just talking and more talking, social-studies lectures by way of rock ‘n’ roll Babylon, at carnival-barker cadence.”

Read the whole thing at Maximum Fun.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Colin Marshall sits down in London’s Tower Hamlets with composer and artist Robin Rimbaud, better known as Scanner. They discuss the usefulness of a new place’s disorientation; the fun of grasping that new place’s systems and making its connections; other skills in the set gained from a lifetime of travel; the “great change” he has observed living in east London for fourteen years, where he arrived in search of “light and high ceilings”; the value of his work’s taking him to places he doesn’t choose; what he learned long ago when his visiting American friend’s girlfriend reflexively called every difference in England “really stupid”; the ease of complaint and the difficulty of embracing these differences; the importance of pattern in all areas of life; the complex question of how to cross a street in Vietnam; travel as a means of seeing your own home; photography as a means of notetaking; his shelves of diaries, kept every single day since age twelve, and what it says about his overarching skill of discipline; self-documentation’s need of a system to give it meaning, and how his famous early Scanner work gave meaning to other people’s phone calls; the intriguing question of how, exactly, you ended up interested in something, friends with someone, or in a place; whether not liking a piece of culture just means you can’t connect anything else to it; the greater fascination of why others love something you don’t love, and the need to experience it all in order to value what you do love; why we had such strong allegiances to music as teenagers; Nick Drake, B.S. Johnson, and the non-connected creator alone against the world; how he facilitates connections himself by staying available at all times; what he listens to in London, especially the local accents and terms of address like “mate,” “love,” and “boss”; how friends visit London and fail to connect to the west end, whereas he remains excited by the rest of the city; and the joy of walking by the historic site of George Orwell’s arrest.

Colin Marshall sits down in London’s Tower Hamlets with composer and artist Robin Rimbaud, better known as Scanner. They discuss the usefulness of a new place’s disorientation; the fun of grasping that new place’s systems and making its connections; other skills in the set gained from a lifetime of travel; the “great change” he has observed living in east London for fourteen years, where he arrived in search of “light and high ceilings”; the value of his work’s taking him to places he doesn’t choose; what he learned long ago when his visiting American friend’s girlfriend reflexively called every difference in England “really stupid”; the ease of complaint and the difficulty of embracing these differences; the importance of pattern in all areas of life; the complex question of how to cross a street in Vietnam; travel as a means of seeing your own home; photography as a means of notetaking; his shelves of diaries, kept every single day since age twelve, and what it says about his overarching skill of discipline; self-documentation’s need of a system to give it meaning, and how his famous early Scanner work gave meaning to other people’s phone calls; the intriguing question of how, exactly, you ended up interested in something, friends with someone, or in a place; whether not liking a piece of culture just means you can’t connect anything else to it; the greater fascination of why others love something you don’t love, and the need to experience it all in order to value what you do love; why we had such strong allegiances to music as teenagers; Nick Drake, B.S. Johnson, and the non-connected creator alone against the world; how he facilitates connections himself by staying available at all times; what he listens to in London, especially the local accents and terms of address like “mate,” “love,” and “boss”; how friends visit London and fail to connect to the west end, whereas he remains excited by the rest of the city; and the joy of walking by the historic site of George Orwell’s arrest.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast I have a conversation with the prolific and philosophical novelist Percival Everett, author of books like Erasure, Assumption, I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Percival Everett by Virgil Russell, and the newly reissued Glyph. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Deep into my exploration of Los Angeles, I took my first trip to London, a city whose built environment one assumes contrasts in the starkest, least flattering way against that of the city I came from. A classic London architectural tour would take you past all the city’s least Los Angelinian aspects: Edwardian buildings lining the Thames, Big Ben, the glories of the neo-Gothic. Eschewing this pathway, I instead wandered without aim into the areas least in line with London’s self-image, all the while reflecting upon the many conversations I’ve had with Brits who’d left this native land of theirs, made a beeline for Los Angeles, and proceeded to enjoy their subsequent absence of regrets. Everyone cites writers like Christopher Isherwood and artists like David Hockney as this movement’s visionaries, and I still find the freshest perspectives of the city from their countless spiritual descendants, even if they’ve lived in Los Angeles a dozen times as long as I have.

You’ll mostly find them in the coastal northwest around Santa Monica, which seems well on its way to spearheading a new generation of British colonies. I rode out there one day to talk with Bath-born architecture and design journalist and broadcaster Frances Anderton on my podcast Notebook on Cities and Culture. Having grown up in a town known for its preservation of the image of one particular, long-gone England, Anderton found in Los Angeles an escape, as many of her countrymen do, from “the crushing burden of history.” And to the city’s ahistorical, untraditional aesthetic tendencies she credits not just the reflection of a kind of freedom, but the production of a kind of beauty.

Read the whole thing on KCET Departures.

Monday, February 17, 2014

My recent, first trip to London presented me with two surprises: the reach, convenience, and frequency of the tube, and the volume of Londoners’ complaints about the reach, convenience, and frequency of the tube.

English friends had explained to me, not without pride, the importance of grumbling to the national character, but I still want to stress to every Londoner I meet that — take it from a visiting Los Angeleno — the tube exists, and that counts as no trifling achievement. Beyond that, and like every other means of urban transport system around the world, it tells you nearly everything you need to know about the city it serves.

If you wish to understand London or any place else, look no further than how people move through it. This goes not just for subways, but overground trains, buses, cycleways, rickshaws, and every mobility solution in between. You can learn a great deal from robust transport systems, and even more from underdeveloped ones.

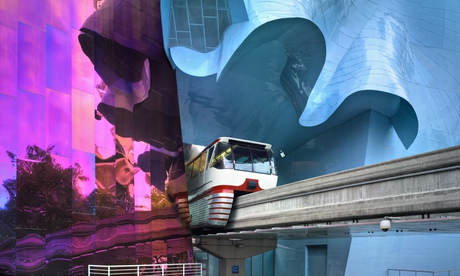

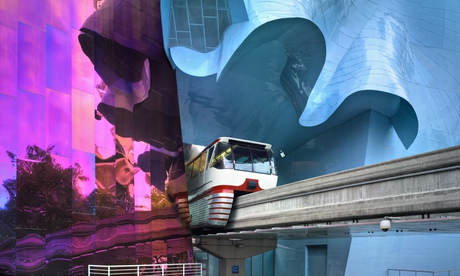

This line of thinking never occurred to me in my years growing up just outside Seattle, a city which I frequented but never gave much thought. Seattle’s “retro-futuristic” image has, for the past half century, rested in large part on a pair of structures built for its 1962 World’s Fair: the globally recognisable Space Needle, and the lesser-known but still sadly evocative monorail. While neither offer much of everyday value to the locals, the monorail – which takes the form but, in running back and forth on only a mile of track, not the function of a dedicated public transit system – stands as a reminder of the city’s many frustrated attempts at complete urbanisation. Proposals for a useful monorail network have risen and fallen over the years; the first light rail line there opened only in 2009.

Read the whole thing at The Guardian.

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Colin Marshall stands around Hackney, London’s “Tech City” with urban designer Euan Mills. They discuss how to tip in a London bar and how to cross a London street; when he realized he has become an urban designer, and what that entails; the hugeness and non-understandability of the spread-out, car-dependent, crime-fearing São Paulo, where he grew up hating cities; the development of his interest in people, not buildings, and cities as networks of people; how he came to London, a city of paradoxes that still gives him the sense that anything exciting that happens will happen there; what, exactly, makes a “high street”; how zoning differences between the U.S. and the U.K. affect neighborhoods, and the sorts of changes he’s seen in London’s in the 21st century; This Isn’t F***ing Dalston, and what it told him about the edges of neighborhoods; how long a place takes to gentrify, and how it then matures, coming to embody all its eras at once; what bars, and the price of a pint of Guinness, tell you about a neighborhood; how everybody likes “authenticity” and nobody likes to feel like a target market; the test of a business you feel uncomfortable entering; what it means then the charity shops, 99p stores, and betting offices start showing up; the change in places like the growth in our hair, so show we don’t notice it; the necessity of combining local experience with placemaking expertise; São Paulo as a repeat of London in the 1960s, and the bad reputation top-down planning developed in that era; what to look for in London, like the intentions of a place or its people; the importance of thinking about who owns the land; and what effect the London weather might have on all this.

Colin Marshall stands around Hackney, London’s “Tech City” with urban designer Euan Mills. They discuss how to tip in a London bar and how to cross a London street; when he realized he has become an urban designer, and what that entails; the hugeness and non-understandability of the spread-out, car-dependent, crime-fearing São Paulo, where he grew up hating cities; the development of his interest in people, not buildings, and cities as networks of people; how he came to London, a city of paradoxes that still gives him the sense that anything exciting that happens will happen there; what, exactly, makes a “high street”; how zoning differences between the U.S. and the U.K. affect neighborhoods, and the sorts of changes he’s seen in London’s in the 21st century; This Isn’t F***ing Dalston, and what it told him about the edges of neighborhoods; how long a place takes to gentrify, and how it then matures, coming to embody all its eras at once; what bars, and the price of a pint of Guinness, tell you about a neighborhood; how everybody likes “authenticity” and nobody likes to feel like a target market; the test of a business you feel uncomfortable entering; what it means then the charity shops, 99p stores, and betting offices start showing up; the change in places like the growth in our hair, so show we don’t notice it; the necessity of combining local experience with placemaking expertise; São Paulo as a repeat of London in the 1960s, and the bad reputation top-down planning developed in that era; what to look for in London, like the intentions of a place or its people; the importance of thinking about who owns the land; and what effect the London weather might have on all this.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

People disagree about what most meaningfully indicates whether a Los Angeles neighborhood has turned “cool.” A seemingly disproportionate number of respected musical acts having emerged from it makes for one early sign. A sudden abundance of galleries and drinking spots there provides further, more solid evidence, amid which a few parking spots may stay open in the evening. Crime, for the most part, moves elsewhere. Its rents will, of course, rise — a force that inevitably renders the place uncool again. Somewhere during this process, the press naturally gets around to covering the neighborhood, and in the pre-internet era we would have said that heralded the beginning of the end; move into a part of town of which the newspapers have already made a big deal, and you’ve come too late.

Not quite so today, when every development, no matter how inconsequential, sends off a ripple of online coverage. My own suspicion that I’d do well to give a neighborhood further consideration emerges when it begins to produce lists, the kind that compile its “Eight Least-Known Concert Venues,” say, or its “Twelve Essential Cocktails,” its “Top Fifteen Highly Artisanal Coffee Experiences,” its “Five Most Authentic Pupuserías.” The growing prevalence of this form, long a mainstay of such bastions of journalistic rigor as Cosmopolitan magazine, doesn’t seem to everyone an entirely positive phenomenon, and most lists do little to hide their sole intention of milking a few clicks from office workers bored halfway to nihilism. Still, used as a delivery system for basic information about what you’ll find where, they may come in handy indeed. As Highland Park figured into more and more of them, I sensed that its moment had come.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo with Dan Kuramoto, founding member of the band Hiroshima who have now played for 40 years and recently released their 19th album, J-Town Beat. They discuss what he sees around him in the Little Tokyo in transition today as opposed to the one he grew up in 40 years ago; what it means to play “Los Angeles music” in this multi-ethnic city; how the band’s koto player June Kuramoto learned her classical instrument while growing up in a Los Angeles black ghetto; the question of whether you can build a modern, western band around the koto, which Hiroshima has always tried to answer; how musical traditions with deeper roots cooperate better together; making their musical mixtures work as, in microcosm, making America work; making the still mutable Los Angeles work as, in microcosm, making America work; his time as an Asian-American Studies department chair at CSU Long Beach, and what he found out about Japanese-Americans there; music as a “way of healing” from the self-hate he once took from the media; his lunch with Ridley Scott and Hans Zimmer; how it felt to become part of a group considered “the bad guys” again in the 1980s, just as Hiroshima really took off; the band’s first trip to Japan, and the visceral feelings it brought about; the universality of craft as an integral part of Japanese identity; the difficulties companies have had categorizing Hiroshima, and the special problems of the “smooth jazz” label; his lack of desire to play music for secretaries who just need their afternoons to pass more quickly; how they honed their chops in the Los Angeles black communities, and how black radio gave them their first big push; and the composition and meaning of the striking cover of their second album, Odori.

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo with Dan Kuramoto, founding member of the band Hiroshima who have now played for 40 years and recently released their 19th album, J-Town Beat. They discuss what he sees around him in the Little Tokyo in transition today as opposed to the one he grew up in 40 years ago; what it means to play “Los Angeles music” in this multi-ethnic city; how the band’s koto player June Kuramoto learned her classical instrument while growing up in a Los Angeles black ghetto; the question of whether you can build a modern, western band around the koto, which Hiroshima has always tried to answer; how musical traditions with deeper roots cooperate better together; making their musical mixtures work as, in microcosm, making America work; making the still mutable Los Angeles work as, in microcosm, making America work; his time as an Asian-American Studies department chair at CSU Long Beach, and what he found out about Japanese-Americans there; music as a “way of healing” from the self-hate he once took from the media; his lunch with Ridley Scott and Hans Zimmer; how it felt to become part of a group considered “the bad guys” again in the 1980s, just as Hiroshima really took off; the band’s first trip to Japan, and the visceral feelings it brought about; the universality of craft as an integral part of Japanese identity; the difficulties companies have had categorizing Hiroshima, and the special problems of the “smooth jazz” label; his lack of desire to play music for secretaries who just need their afternoons to pass more quickly; how they honed their chops in the Los Angeles black communities, and how black radio gave them their first big push; and the composition and meaning of the striking cover of their second album, Odori.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

Though you can no longer go to a Japanese department store on the Miracle Mile, you can go to one in Hollywood. Half a century after Seibu took leave of Los Angeles, Muji arrived, representing the current shopping generation as thoroughly as its predecessor represented its own. Seibu, which in its native country harks far back, and far away, to the lavish department stores of fin-de-siècle Europe, theoretically dovetailed right in with the automobile-oriented, fully enclosed shopping experience, which developed so rapidly in postwar America in general and Southern California in particular. Why it didn’t take nobody can quite say, though at that time the country still regarded things Japanese as a novelty, and by the early 1960s traditional department stores, even those out on the “suburban” stretches of Wilshire Boulevard, had already ground to much larger, even farther-flung suburban malls, against whose comfortable convenience even the grandness of Seibu proved no match.

Despite occupying more square footage than any other branch in America, Hollywood’s Muji, by contrast, looks like a utilitarian, almost bare-bones operation. Clothes, snacks, housewares, gadgetry — all of it occupies a single floor, and little separates one type of product from another in placement, design, or (often nonexistent) packaging. Everything at Muji shares the family resemblance of maximum simplicity, a deceptively rigorous aesthetic reassuring shoppers that they haven’t paid for frivolity, for display, for bells and whistles. A far cry indeed from the days when opulence sold in quantity, and one whose number of eager respondents signals the definitive end of the developed world’s previous cycle of big spending. Muji’s product shows us something about the new vogue — for what we in America and Japan like to think of as the old, unwasteful virtues — but, given the newest wave of city life, so does its location.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Thursday, January 30, 2014

On the northwest side of Glendale Boulevard, Kaldi Coffee, which boasts a signature brew from beans “roasted locally in Atwater Village,” hosts a long-sitting procession of the unconventionally employed, customers in sometimes dire need of both caffeine to power their brains and electricity to power their laptops. (Indeed, it once provided all the material for a Los Angeles Times human-interest story on the lives of aspiring to mid-level screenwriters.) On the southeast side, Proof Bakery, though it also serves a fine cappuccino and an even better scone, offers neither outlets nor bathrooms, encouraging their clientele, and their precocious young children often in tow, to move briskly through. Such specialization of the already specialized now happens in this neighborhood way up in the northeast, which some rank as the “hippest” in Los Angeles, some either dismiss or applaud as a “brunch zone,” and some describe as the closest experience the city offers to the professionally lighthearted, indie-everything sensibility of Portland, Oregon.

Some may explain their move to Atwater Village by admitting that it lets them live a mildly suburbanized life without having to actually move into a suburb. Throughout much of the twentieth century, the whole of Los Angeles held out this same promise: maybe, just maybe, you could here have the cake of a comfortable lifestyle, while also eating the cake of culturally robust and environmentally stimulating surroundings. To this day, nobody has quite figured out whether to declare that an oasis or a mirage. But those seeking that elusive midpoint between crowded but exhilarating city center, and comfortable if sense-dulling bedroom community, have lately found their moving target hovering around the northeastern corner of Los Angeles, where Atwater Village perhaps stands as the frontier.

Read the whole thing at KCET Departures.

Colin Marshall sits down in London’s Tower Hamlets with composer and artist Robin Rimbaud, better known as

Colin Marshall sits down in London’s Tower Hamlets with composer and artist Robin Rimbaud, better known as

Colin Marshall stands around Hackney, London’s “Tech City” with urban designer

Colin Marshall stands around Hackney, London’s “Tech City” with urban designer

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo with Dan Kuramoto, founding member of the band

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo with Dan Kuramoto, founding member of the band