Colin Marshall sits down under the cafeteria at Santa Monica College with beloved Los Angeles radio personality Madeleine Brand, now host of Press Play on KCRW, formerly of NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and Day to Day, KPCC’s The Madeleine Brand Show, and KCET’s SoCal Connected. They discuss how much easier she has it waking up for noon radio nowadays instead of morning radio; what to call her format, a popular one in Los Angeles, where one host talks to a series of people, each with their own thing going on in the news; the distinctive difficulty of finding subjects that interest a large percentage of Los Angeles; her first decade in Southern California, and her later college years in Northern California as KALX’s “Madame Bomb”; Los Angeles’ unusually close relationship with the radio; the east-coastification she experienced in her years amid the “visceral humanity” of New York; how the heightening, densifying Los Angeles we see on the way (and imagined in Her) strikes her inner New Yorker; her lingering nostalgia for the sense of “peace, openness, and quiet” that formerly characterized this city; how we might allow Los Angeles to both define itself and not define itself, retaining its borderlessness with the rest of the world; how she’s solved part of the hours-in-the-day problem (and the traffic problem) by hiring a driver; the asshole each and every one of us turns into when we get behind the wheel ourselves; what, exactly, makes for a “news story”; her task of making a subject meaningful beyond the first thirty seconds; the grim public radio listener’s moment of realization that they’re trying to guess what interests you; the mechanics of a five-minute interview (featuring an actual, table-turning five-minute interview); how often complaints come from a legitimate argument, and how often they come from a bad life; how easy Los Angeles makes it to live a bad life; the missing types of public discourse she’d like to hear in Los Angeles; the sorts of problems that public discourse can help to solve, such as school segregation; and whether to call him “Smokey Bear” or “Smokey the Bear.”

Colin Marshall sits down under the cafeteria at Santa Monica College with beloved Los Angeles radio personality Madeleine Brand, now host of Press Play on KCRW, formerly of NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and Day to Day, KPCC’s The Madeleine Brand Show, and KCET’s SoCal Connected. They discuss how much easier she has it waking up for noon radio nowadays instead of morning radio; what to call her format, a popular one in Los Angeles, where one host talks to a series of people, each with their own thing going on in the news; the distinctive difficulty of finding subjects that interest a large percentage of Los Angeles; her first decade in Southern California, and her later college years in Northern California as KALX’s “Madame Bomb”; Los Angeles’ unusually close relationship with the radio; the east-coastification she experienced in her years amid the “visceral humanity” of New York; how the heightening, densifying Los Angeles we see on the way (and imagined in Her) strikes her inner New Yorker; her lingering nostalgia for the sense of “peace, openness, and quiet” that formerly characterized this city; how we might allow Los Angeles to both define itself and not define itself, retaining its borderlessness with the rest of the world; how she’s solved part of the hours-in-the-day problem (and the traffic problem) by hiring a driver; the asshole each and every one of us turns into when we get behind the wheel ourselves; what, exactly, makes for a “news story”; her task of making a subject meaningful beyond the first thirty seconds; the grim public radio listener’s moment of realization that they’re trying to guess what interests you; the mechanics of a five-minute interview (featuring an actual, table-turning five-minute interview); how often complaints come from a legitimate argument, and how often they come from a bad life; how easy Los Angeles makes it to live a bad life; the missing types of public discourse she’d like to hear in Los Angeles; the sorts of problems that public discourse can help to solve, such as school segregation; and whether to call him “Smokey Bear” or “Smokey the Bear.”

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

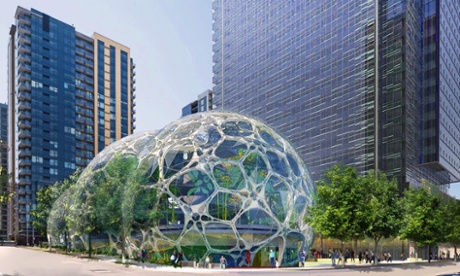

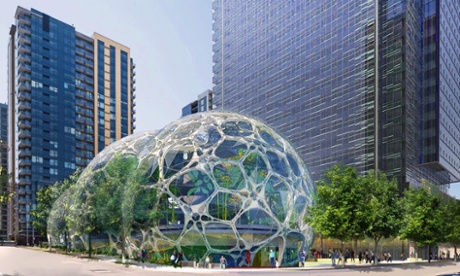

I often told myself in adolescence that, even though I’d had to grow up in a none-too-exciting Seattle suburb, at least my particular none-too-exciting Seattle suburb boasted the headquarters of both Microsoft and Nintendo of America. Though I had to ride my bike for the better part of an hour to reach so much as a grocery store, at least I could feel, or imagine I felt, the buzz of thrilling new computer and entertainment technologies in development not far away.

Nintendo established its Redmond, Washington campus in 1982; Microsoft moved its headquarters there in 1986. Both years fall squarely within the late stage of America’s long period of suburbanisation, when people and corporations alike pulled their stakes up from the country’s once-robust city centres and put them down in far-flung suburbs like Redmond, which back in the 1980s turned nearly rural at its edges. Taking my thrills where I could find them in such an environment, I seized every opportunity to visit their leafy compounds.

I still remember the awe I felt upon entering these tightly secured, painstakingly landscaped worlds-unto-themselves. They looked intent on addressing their employees’ every need, thereby absolving them of the obligation to stray from campus. Many a story circulated of life at Microsoft headquarters, where programmers would supposedly keep themselves awake and coding on deadline for days at a stretch with endless company-supplied cafeteria meals and bottles of Jolt Cola. (Douglas Coupland would satirise this cutting-edge-yet-womblike environment of dependency in his 1995 novel, Microserfs.)

Microsoft and Nintendo’s decision to base themselves 15 miles east and across a lake from the city, to say nothing of aerospace giant Boeing’s presence more than 20 miles to the north, did little to benefit Seattle proper. With the region’s economic powers so far out on the periphery, the downtown area fell to what looked like a subservient position before its own suburbs: in parts strangely underdeveloped, in others almost forgotten.

The city’s now-fearsome internet retail pioneer, Amazon.com , might well have continued this saga of corporations key to Seattle’s identity maintaining a distance, and detachment, from the city itself, had it stayed in the even wealthier suburb of Bellevue where the company began (in chief executive Jeff Bezos’s converted garage). Instead, the decision to consolidate much of its headquarters right up against Seattle’s downtown, in a former car-dealer-and-warehouse district called South Lake Union (the lake separates the city’s north and south halves), has engendered a fascinating case study, still very much in progress, of what happens when a powerful company goes about ambitiously building an environment not away and sealed off from the nearest urban centre, but right there in it – and even, to an extent, integrated with it.

Read the whole thing at The Guardian Cities.

I talk with Leslie Jamison, author of the novel The Gin Closet and the new essay collection The Empathy Exams, which features pieces on her experiences acting out disease symptoms for medical students to diagnose, watching the Paradise Lost documentaries, assembling a “grand unified theory of female pain,” and getting mugged in Nicaragua. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

“LOS ANGELES may be the ultimate city of our age.” So begins the 20th century’s most unjustly forgotten book on Los Angeles, written by one of its most unjustly forgotten writers of place. Christopher Rand’s Los Angeles: The Ultimate City appeared in 1967, published by Oxford University Press and built upon a trilogy of articles TheNew Yorker ran in October 1966. Rand began writing for that magazine in 1947, with a piece on the Americans, including himself, who spent World War II nearly unsupervised in Japanese-surrounded southeast China. His last piece for them appeared in 1968, the year he died — observations on the run-up to Mexico City’s Olympics. For those 20 years, in his capacity as TheNew Yorker’s “far-flung correspondent,” he strove to understand what seems, given such a truncated life and career, an unprecedented variety of places, including Hong Kong, Greece, Puerto Rico, Bethlehem, Cambridge, and again and again over the years his own hometown of Salisbury, Connecticut.

“He was a great walker and a far wanderer,” writes Wallace White in Rand’s October 1968 New Yorker obituary.

Over more than 30 years, he traveled to almost every part of the world, doing most of his traveling on foot, in an attempt to learn and know that transcended any effort at mere reporting, and when he died, he was still involved in the search that had occupied most of his life.

In Grecian Calendar, his 1962 book on a year’s exploration of Greece (often conducted on its dusty roads and rocky trails), Rand himself illuminates this method:

I have walked a good deal for years now. I have theories about why one should do it — that it is good for the health, is conducive to thought, makes one able to observe things close at hand, etc. — and I think all these arguments are sound, but the main point is simply that I enjoy walking; I feel calm and happy while doing it.

A few pages later, Rand extends his theory further: “I claim that if one walks with any gusto one is respected by other walkers, and I even boast that it is a good thing, nationalistically, to have a few Americans walking about in far countries. It explodes the generalization that we have forgotten how.” Still, he seems never to have fully identified with his homeland, not least because he spent so much of his career outside it: he left a reporting job at the San Francisco Chronicle in 1943, in his early 30s, for a post in China as a US Office of War Information correspondent. After the war, he continued reporting on China for the New York Herald Tribune until 1951, by which point he had already begun his stretch at TheNew Yorker, where he contributed 64 detailed, long-form essays — detailed and long-form even by The New Yorker’s midcentury standard — each of them revealing, to him and to us, a new place, or a new aspect of a familiar one.

Read the whole thing at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Miracle Mile district with photographer Mark Edward Harris, author of such books as Inside North Korea, Inside Iran, The Art of the Japanese Bath, and Faces of the Twentieth Century. They discuss filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s introduction to his Iran book, and his rule about always excluding people from his own photographs; the importance of children in images of Iran and countries like it; how Bruce Lee may or may not have started his interest in Asia back in his San Francisco childhood; how his job on The Merv Griffin Show came to an end, leaving him free to travel the world and build up his first real portfolio; how he once processed film while traveling, and the lasting thrill he got from first seeing an image appear in the developer; when and how digital cameras first became acceptable; what he learned from Stanley Kubrick’s early journalistic work with Look magazine (not to mention from Dr. Strangelove); the countries, of the 90 he has visited, that he finds himself returning to again and again; the restrictions he has to work under when shooting in North Korea; whether the two Koreas still feel in any way connected to him; his interest in revealing the realities of the nations once named as members of the “Axis of Evil”; why Iranian men tend to look like they stepped out of the 1970s; his relationship with the “discipline and quiet fortitude” of Japan; how he managed to get into Japanese baths with a camera; whether America’s center of Asia gravity has shifted to Los Angeles, a city friendly to the internationalist; how little work he thinks he’s done here, and how much he actually has; and late May’s Fotofund campaign for his new Iran project.

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Miracle Mile district with photographer Mark Edward Harris, author of such books as Inside North Korea, Inside Iran, The Art of the Japanese Bath, and Faces of the Twentieth Century. They discuss filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s introduction to his Iran book, and his rule about always excluding people from his own photographs; the importance of children in images of Iran and countries like it; how Bruce Lee may or may not have started his interest in Asia back in his San Francisco childhood; how his job on The Merv Griffin Show came to an end, leaving him free to travel the world and build up his first real portfolio; how he once processed film while traveling, and the lasting thrill he got from first seeing an image appear in the developer; when and how digital cameras first became acceptable; what he learned from Stanley Kubrick’s early journalistic work with Look magazine (not to mention from Dr. Strangelove); the countries, of the 90 he has visited, that he finds himself returning to again and again; the restrictions he has to work under when shooting in North Korea; whether the two Koreas still feel in any way connected to him; his interest in revealing the realities of the nations once named as members of the “Axis of Evil”; why Iranian men tend to look like they stepped out of the 1970s; his relationship with the “discipline and quiet fortitude” of Japan; how he managed to get into Japanese baths with a camera; whether America’s center of Asia gravity has shifted to Los Angeles, a city friendly to the internationalist; how little work he thinks he’s done here, and how much he actually has; and late May’s Fotofund campaign for his new Iran project.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law with Ethan Elkind, an attorney who researches and writes on environmental law and the author of Railtown: The Fight for the Los Angeles Metro Rail System and the Future of the City. They discuss the reason visitors and even some Angelenos express surprise at the very existence of the city’s subway; the roots of the assumption that Los Angeles would always have a 1950s-style “car culture”; why something as essential as a rail system has required a “fight”; the persistent Roger Rabbit conspiracy theory about the dismantling of Los Angeles’ first rail transit network; why so may, for so long, failed to consider the city’s inevitably dense and increasingly less car-compatible future; Los Angeles’ long-standing anxiety about joining the ranks of “world-class” cities, and how the absence of a subway fueled it; how Californian rail systems, Los Angeles’ especially but the San Francisco’s Bay Area’s BART as well, physically embody the compromises of consensus-based politics; what some Angelenos mean when they talk about “Manhattanization”; the similarity between a city’s expectation that its citizens all own their own cars and an expectation that they all own their own power generators; how much the conversation about rail in Los Angeles has to do with, simply, density in Los Angeles; why Metro pretends not to know about its own problems and resorts to “corporate PR-speak”; whether those who lament the limitations of Los Angeles rail can blame individuals (such as Henry Waxman); whether anyone can change the minds of Angelenos who want the city to return to 1962; the demoralizing effects of such far-flung completion dates as 2036 for the Purple Line subway to UCLA; and how every voter can come to consider the Los Angeles Metro rail system “a precious thing.”

Colin Marshall sits down at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law with Ethan Elkind, an attorney who researches and writes on environmental law and the author of Railtown: The Fight for the Los Angeles Metro Rail System and the Future of the City. They discuss the reason visitors and even some Angelenos express surprise at the very existence of the city’s subway; the roots of the assumption that Los Angeles would always have a 1950s-style “car culture”; why something as essential as a rail system has required a “fight”; the persistent Roger Rabbit conspiracy theory about the dismantling of Los Angeles’ first rail transit network; why so may, for so long, failed to consider the city’s inevitably dense and increasingly less car-compatible future; Los Angeles’ long-standing anxiety about joining the ranks of “world-class” cities, and how the absence of a subway fueled it; how Californian rail systems, Los Angeles’ especially but the San Francisco’s Bay Area’s BART as well, physically embody the compromises of consensus-based politics; what some Angelenos mean when they talk about “Manhattanization”; the similarity between a city’s expectation that its citizens all own their own cars and an expectation that they all own their own power generators; how much the conversation about rail in Los Angeles has to do with, simply, density in Los Angeles; why Metro pretends not to know about its own problems and resorts to “corporate PR-speak”; whether those who lament the limitations of Los Angeles rail can blame individuals (such as Henry Waxman); whether anyone can change the minds of Angelenos who want the city to return to 1962; the demoralizing effects of such far-flung completion dates as 2036 for the Purple Line subway to UCLA; and how every voter can come to consider the Los Angeles Metro rail system “a precious thing.”

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with architect and urban designer Doug Suisman, author of Los Angeles Boulevard: Eight X-Rays of the Body Public, soon out in a new 25th anniversary edition. They discuss the difference in cycling to his office on Wilshire Boulevard versus Venice Boulevard; the conceptual importance of “path” and “place” in any urbanism-related discussion he gets into; his arrival in Los Angeles in 1983, after years spent in Paris and New York, and the mixture of disappointment and fascination he first felt on the boulevards here; what it meant that he sensed movement as well as abandonment; how Los Angeles wound up with the its destructive-car-culture rap, and how its freeways have less to do with that than the way its boulevards also became a kind of freeway system; the mistaken notion that the city “doesn’t have transit,” and what specific kinds of transit it actually does still lack; his work with the design of the Metro Rapid buses, and why they’ve struggled so long just to get a dedicated lane; the combined optimism and complacency of Los Angeles in the 1980s, before any rapid transit had appeared; the excitement he first felt at the the city’s private architectural boom, despite its seeming lack of a public realm; how Los Angeles has begun to overcome its “enclave instinct” and find an “urban public language” as Amsterdam did in the 1930s; the importance of the Olympics, MOCA, LACMA’s Anderson Wing, and now the Ace Hotel’s opening in downtown, that “50-year overnight sensation”; what caused Wilshire’s “wig district”; what his childhood trips from his suburban home to downtown Hartford, Connecticut taught him about city life; coffee shops as harbingers of human connectedness; the basic differences between “apartment cultures” and “house cultures,” and how a city moves from one to the other; and the way the boulevards fit into the psychological framework of Los Angeles alongside the mountains and the ocean.

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with architect and urban designer Doug Suisman, author of Los Angeles Boulevard: Eight X-Rays of the Body Public, soon out in a new 25th anniversary edition. They discuss the difference in cycling to his office on Wilshire Boulevard versus Venice Boulevard; the conceptual importance of “path” and “place” in any urbanism-related discussion he gets into; his arrival in Los Angeles in 1983, after years spent in Paris and New York, and the mixture of disappointment and fascination he first felt on the boulevards here; what it meant that he sensed movement as well as abandonment; how Los Angeles wound up with the its destructive-car-culture rap, and how its freeways have less to do with that than the way its boulevards also became a kind of freeway system; the mistaken notion that the city “doesn’t have transit,” and what specific kinds of transit it actually does still lack; his work with the design of the Metro Rapid buses, and why they’ve struggled so long just to get a dedicated lane; the combined optimism and complacency of Los Angeles in the 1980s, before any rapid transit had appeared; the excitement he first felt at the the city’s private architectural boom, despite its seeming lack of a public realm; how Los Angeles has begun to overcome its “enclave instinct” and find an “urban public language” as Amsterdam did in the 1930s; the importance of the Olympics, MOCA, LACMA’s Anderson Wing, and now the Ace Hotel’s opening in downtown, that “50-year overnight sensation”; what caused Wilshire’s “wig district”; what his childhood trips from his suburban home to downtown Hartford, Connecticut taught him about city life; coffee shops as harbingers of human connectedness; the basic differences between “apartment cultures” and “house cultures,” and how a city moves from one to the other; and the way the boulevards fit into the psychological framework of Los Angeles alongside the mountains and the ocean.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down at Monocle magazine’s offices in Marylebone, London with Andrew Tuck, editor of the magazine, host of its podcast The Urbanist, and editor of its book The Monocle Guide to Better Living. They discuss how the London experience for a Monocle reader differs from that of others; how the magazine came to view the world through the framework of cities, and what they look for in a good city experience; the importance of aesthetics in all things, when aesthetics means stripped-down, timeless vitality rather than whatever more and more money can buy; the importance of slowness in everything Monocle touches; the magazine’s launch in 2007, the global economic crash that happened soon thereafter, and why it began to matter even more that they covered “tangible things”; his notion that every Monocle reader has a business in them; what he found when he first came to live in London at eighteen; what he sees on his 40-minute walk to work each day, always on a different route; the city’s internationalism, and what it affords an outfit like Monocle; how the prediction that the internet age would render it no longer necessary to meet people has turned into “nonsense”; the origin of the Urbanist podcast, and the episode of that show which reversed interviewer and interviewee; the “terrible trend of thinking all cities are kind of the same”; why the likes of Copenhagen, Melbourne, and Zurich rank so high on Monocle‘s quality of life survey; urban “wildcards” like Naples, Beirut, and Buenos Aires, which have the advantage of the “intangible”; what, exactly, the magazine has always seen in Japan; the cities that continue to generate questions, such as New York (and not “the New York people pretend they loved in the seventies”); the charge against Monocle‘s “aspirational” nature, and why anyone would think that a liability; the more established media companies who have stopped doing journalism in favor of “navigating the downward spiral of their titles”; the organic, human-like nature of London that still surprises; and how he wants to see whether the city grows old with him.

Colin Marshall sits down at Monocle magazine’s offices in Marylebone, London with Andrew Tuck, editor of the magazine, host of its podcast The Urbanist, and editor of its book The Monocle Guide to Better Living. They discuss how the London experience for a Monocle reader differs from that of others; how the magazine came to view the world through the framework of cities, and what they look for in a good city experience; the importance of aesthetics in all things, when aesthetics means stripped-down, timeless vitality rather than whatever more and more money can buy; the importance of slowness in everything Monocle touches; the magazine’s launch in 2007, the global economic crash that happened soon thereafter, and why it began to matter even more that they covered “tangible things”; his notion that every Monocle reader has a business in them; what he found when he first came to live in London at eighteen; what he sees on his 40-minute walk to work each day, always on a different route; the city’s internationalism, and what it affords an outfit like Monocle; how the prediction that the internet age would render it no longer necessary to meet people has turned into “nonsense”; the origin of the Urbanist podcast, and the episode of that show which reversed interviewer and interviewee; the “terrible trend of thinking all cities are kind of the same”; why the likes of Copenhagen, Melbourne, and Zurich rank so high on Monocle‘s quality of life survey; urban “wildcards” like Naples, Beirut, and Buenos Aires, which have the advantage of the “intangible”; what, exactly, the magazine has always seen in Japan; the cities that continue to generate questions, such as New York (and not “the New York people pretend they loved in the seventies”); the charge against Monocle‘s “aspirational” nature, and why anyone would think that a liability; the more established media companies who have stopped doing journalism in favor of “navigating the downward spiral of their titles”; the organic, human-like nature of London that still surprises; and how he wants to see whether the city grows old with him.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

On the latest Los Angeles Review of Books podcast, I talk with comic artist Mimi Pond, author of a variety of books from The Valley Girl’s Guide to Life to the new Over Easy, a graphic novel based on her waitressing days in late-1970s Oakland. You can listen to the conversation on the LARB’s site, or download it on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down in Knightsbridge, London with Jacques Testard, founding editor of the quarterly arts journal The White Review. They discuss the re-issue of Nairn’s Towns featuring past guest Owen Hatherley; London’s surprisingly small literary culture and what, before founding The White Review, he didn’t see getting published; the “deeply stereotypical Williamsburg existence” he once lived in New York (in an apartment called “Magicland”, no less); his path from his hometown of Paris to London, and what those cities throw into contrast about each other; the conversations he’s had with his also-bilingual brother about the differences between reading and speaking English and French, and the fact that they can take both languages “on their own terms”; the lack of genre distinctions in the French literary market; the amount of material The White Review publishes in translation; how a 21st-century magazine must, above all else, avoid disposability; the interviews they run, with Will Self and others; a “good writer’s” ability to transcend subject matter; the engagement and/or existence strategies that apply in New York versus those that apply in London; class in Britain as tied to education, and class in America as tied to money; his experience at the Jaipur Literary Festival; and what to expect in The White Review‘s current issue.

Colin Marshall sits down in Knightsbridge, London with Jacques Testard, founding editor of the quarterly arts journal The White Review. They discuss the re-issue of Nairn’s Towns featuring past guest Owen Hatherley; London’s surprisingly small literary culture and what, before founding The White Review, he didn’t see getting published; the “deeply stereotypical Williamsburg existence” he once lived in New York (in an apartment called “Magicland”, no less); his path from his hometown of Paris to London, and what those cities throw into contrast about each other; the conversations he’s had with his also-bilingual brother about the differences between reading and speaking English and French, and the fact that they can take both languages “on their own terms”; the lack of genre distinctions in the French literary market; the amount of material The White Review publishes in translation; how a 21st-century magazine must, above all else, avoid disposability; the interviews they run, with Will Self and others; a “good writer’s” ability to transcend subject matter; the engagement and/or existence strategies that apply in New York versus those that apply in London; class in Britain as tied to education, and class in America as tied to money; his experience at the Jaipur Literary Festival; and what to expect in The White Review‘s current issue.

Download the interview here as an MP3 or on iTunes.

Colin Marshall sits down under the cafeteria at Santa Monica College with beloved Los Angeles radio personality Madeleine Brand, now host of Press Play on KCRW, formerly of NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and Day to Day, KPCC’s The Madeleine Brand Show, and KCET’s SoCal Connected. They discuss how much easier she has it waking up for noon radio nowadays instead of morning radio; what to call her format, a popular one in Los Angeles, where one host talks to a series of people, each with their own thing going on in the news; the distinctive difficulty of finding subjects that interest a large percentage of Los Angeles; her first decade in Southern California, and her later college years in Northern California as KALX’s “Madame Bomb”; Los Angeles’ unusually close relationship with the radio; the east-coastification she experienced in her years amid the “visceral humanity” of New York; how the heightening, densifying Los Angeles we see on the way (and imagined in Her) strikes her inner New Yorker; her lingering nostalgia for the sense of “peace, openness, and quiet” that formerly characterized this city; how we might allow Los Angeles to both define itself and not define itself, retaining its borderlessness with the rest of the world; how she’s solved part of the hours-in-the-day problem (and the traffic problem) by hiring a driver; the asshole each and every one of us turns into when we get behind the wheel ourselves; what, exactly, makes for a “news story”; her task of making a subject meaningful beyond the first thirty seconds; the grim public radio listener’s moment of realization that they’re trying to guess what interests you; the mechanics of a five-minute interview (featuring an actual, table-turning five-minute interview); how often complaints come from a legitimate argument, and how often they come from a bad life; how easy Los Angeles makes it to live a bad life; the missing types of public discourse she’d like to hear in Los Angeles; the sorts of problems that public discourse can help to solve, such as school segregation; and whether to call him “Smokey Bear” or “Smokey the Bear.”

Colin Marshall sits down under the cafeteria at Santa Monica College with beloved Los Angeles radio personality Madeleine Brand, now host of Press Play on KCRW, formerly of NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered, and Day to Day, KPCC’s The Madeleine Brand Show, and KCET’s SoCal Connected. They discuss how much easier she has it waking up for noon radio nowadays instead of morning radio; what to call her format, a popular one in Los Angeles, where one host talks to a series of people, each with their own thing going on in the news; the distinctive difficulty of finding subjects that interest a large percentage of Los Angeles; her first decade in Southern California, and her later college years in Northern California as KALX’s “Madame Bomb”; Los Angeles’ unusually close relationship with the radio; the east-coastification she experienced in her years amid the “visceral humanity” of New York; how the heightening, densifying Los Angeles we see on the way (and imagined in Her) strikes her inner New Yorker; her lingering nostalgia for the sense of “peace, openness, and quiet” that formerly characterized this city; how we might allow Los Angeles to both define itself and not define itself, retaining its borderlessness with the rest of the world; how she’s solved part of the hours-in-the-day problem (and the traffic problem) by hiring a driver; the asshole each and every one of us turns into when we get behind the wheel ourselves; what, exactly, makes for a “news story”; her task of making a subject meaningful beyond the first thirty seconds; the grim public radio listener’s moment of realization that they’re trying to guess what interests you; the mechanics of a five-minute interview (featuring an actual, table-turning five-minute interview); how often complaints come from a legitimate argument, and how often they come from a bad life; how easy Los Angeles makes it to live a bad life; the missing types of public discourse she’d like to hear in Los Angeles; the sorts of problems that public discourse can help to solve, such as school segregation; and whether to call him “Smokey Bear” or “Smokey the Bear.”

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Miracle Mile district with photographer

Colin Marshall sits down in Los Angeles’ Miracle Mile district with photographer  Colin Marshall sits down at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law with

Colin Marshall sits down at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law with  Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with architect and urban designer

Colin Marshall sits down in Santa Monica with architect and urban designer